On August 8th, Presidential Candidate Bernie Sanders held a rally in Seattle that was brought to a halt by protesters for the Black Lives Matter movement. The protesters were met with insults and disdain from the audience as they spoke. Sophie Aanerud talks about how she felt about the protesters’ sudden arrival.

To Marissa Johnson,

Firstly, an introduction: I have lived my entire life in Seattle. I am white, raised in a decidedly progressive, educated, middle-class household. My mother analyzes and teaches race and sexuality studies; she wrote her doctoral dissertation on the problematic narratives brought forth through white liberalism, focusing especially upon white liberal feminism. Discussions around the dinner table often focused on class and racial divisions, exploring the many ways white privilege had impacted my life. And it has; in nearly every element of my life one can find traces of privilege based on my skin, my ethnic background. I am white. I am privileged. I have spent much of my adolescence pondering how to use this privilege.

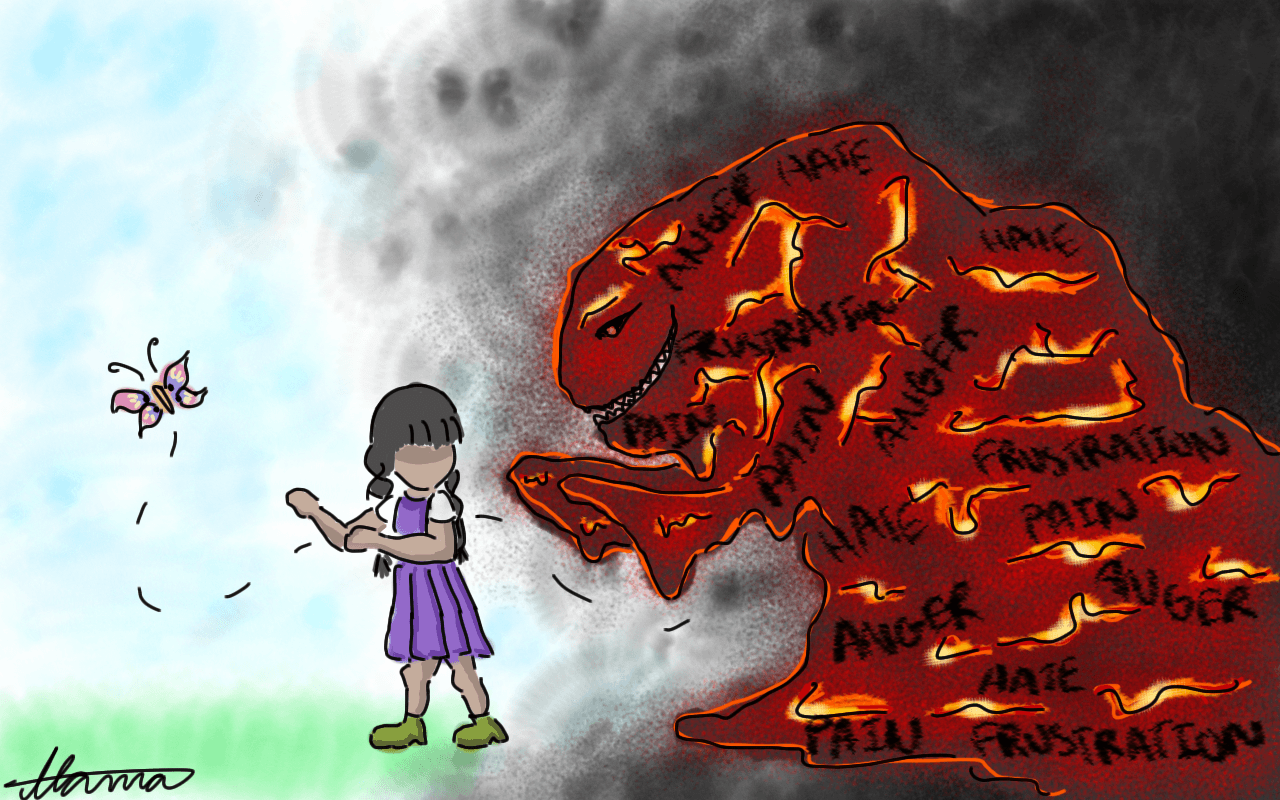

I mainly wish to talk to you about anger. When I first heard of the interruption of the Bernie Sanders event by protesters aligned with the Black Lives Matter movement, I was angry. Angry for several reasons, some justifiable, some not. I was angered by the apparent disrespect these activists were showing a man who had become one of my political heroes. I was angered to think of the hard work put into organizing this important rally, focused on such important issues, was rendered more or less a failure. I was angered that whatever wisdom Bernie had to share with my city was left unuttered. This anger is justifiable.

I was also angered by the words of the protesters. Angered to hear someone so vehemently speaking of my city in a negative light. I love Seattle with passion; so often we want to see the object of our love exclusively as perfect. I was taken aback, offended when you, Ms. Johnson, labeled this place I so love as “racist.” I furthermore took this statement recognizing the racism in white Seattle as a personal attack on myself, on my parents who have put forth so much effort so as to keep their daughter from falling into the self-affirming world of white liberalism. “How dare she ignore their work? How dare this stranger not take into account my story?” This anger was not justifiable.

Slowly I am working to listen. To extend beyond my own misplaced white fragility, and focus instead upon your words. There was so much truth in your speech. Seattle is a hub for race-related inequalities. The white liberal majority allows these injustices to continue. I allow them to continue. And especially as an individual who reaps the benefits of such injustice, it is uncomfortable for me to hear this. I have been more challenged on such topics of race-discrimination than many, but I still often creep back into my bubble of white liberal blamelessness.

Even my minimal justifiable anger related to the protest has made it hard for me. Hard to understand and eventually drop my unjustifiable anger. Hard for me to focus on the actual content of your speech.

So now for an exploration of anger: namely justified anger versus unjustifiable anger. Anger that stems from actions not warranting of such a response— unjustified anger— eases swiftly, melting in the face of truth, if unencumbered by the other form of anger— justifiable anger. This anger is not without its uses. There is, as explained by Audre Lorde in her article, “The Uses of Anger,” information which can be gleaned through the recognition of this type of anger. Such being said, justified anger lasts longer, holds more power. It features the power to shield its possessor not only from the truth, but from conceiving the flagrant roots of any unjustifiable anger. Through anger, we slide into antagonistic tendencies, labeling any individual causing us anger of any form as an enemy. Under this anger, we no longer can identify commonalities.

Like its kin, violence, no steady peace and understanding can come from actions rooted in anger of any form.

Ms. Johnson, what I am suggesting you do is wholeheartedly unfair. You have so much justification for your anger. The BLM movement has so much justification for anger. Black America, America in general has justification for anger. Innocent individuals are on the daily targets of police brutality based simply on their skin color. Black culture is used by the privileged white population as a form of entertainment. This country is ruled by an arbitrary caste system rooted in hundreds of years of cruelty and politicians are doing very little, if anything, to change this. You have every reason to be angry. Despite this righteousness, I am concerned that this anger may be in fact impeding upon your ability to make the change we so long to see.

I can only speak from my own perspective, but as I watched again and again the footage of the Bernie Sanders protest, as my justified and unjustified anger slowly eased, I began to see you. Finally I was seeing you less as the antagonist sculpted by my own anger, but as a woman desperate to see change, a woman with important things to say, but also a woman consumed by anger.

I wonder what could be achieved if you were to work outside of your justified anger, to see those who may lack sophisticated understandings of race relations and whose minds you are working to help expand not as your enemies. I wonder what could be achieved if you were to allow them to speak, allow yourself to listen. In order to succeed in establishing real change, we must not let our conversations be one-sided.

From my perspective, the protest and the Bernie Sanders event came from a place of anger, a point where those involved, on all sides, allowed their anger to paint the situation in shades of antagonism. I responded with anger. The crowd responded with anger. You responded with anger. Little is accomplished.

Especially when dealing with topics which will cause discomfort and force individuals—especially the privileged— to confront their own roles in said subjects, it is crucial we cast aside all anger. Humans struggle when they are faced with such an “uncomfortable” reality; any anger present will halt the necessary struggle. They will cease to listen, cease to look.

Anger will always exist, but true lasting change can only come with love. And so I ask that you try to keep your anger from impacting your actions. I will try to do the same.

With growing respect,

Sophie Aanerud

Featured Picture by Jyoti Lama

I think you are wrong.

I forgot to put a link to the supporting article. http://www.alternet.org/news-amp-politics/why-ignorant-white-americans-are-terrified-angry-black-people

Don’t let the title scare you. Please just read it, it will help you understand even better. Policing the way black people are allowed to express anger is as old as this nation. Hiding the justifyable anger allows us to be dehumanized, or superhumanized, imo.

To bravenak,

Thank you for the article. I can very much understand the argument it puts forth and I found myself, while writing this piece, often wondering how my argument may play into the (as the article you posted puts) “branding with a veritable scarlet letter” of African Americans, especially African American women, who show their anger, as “angry black people.” In all honesty, I was uncertain how to address this topic of public black anger. I found the line in the article explaining that “one of the greatest privileges that comes with being ‘white’ in America is the permission and encouragement to hold onto a sense of injustice, grievance, anger, and pain” very helpful in articulating this disparity which I have never quite understood. I also agree that in this country, the concept of “black forgiveness” explained in the article is a type of bandage which keeps white Americans firstly from noting injustices performed in the past and how these injustices impact their lives, while simultaneously keeping them from growing and taking efforts to eliminate the effects of these injustices in the future. Now I do first off believe that forgiveness is crucial, and that all individuals must in some ways recognize the humanity in those who have done great wrongs against them and that this country should hold with higher regards the concept of forgiveness and extend this as an, dare I say, “expectation” for all Americans, in the reconciliation respect as modeled by South Africa’s post-Apartheid Truth and Reconciliation movement. Maybe this is unfair; maybe we as a species have not reached a point where forgiveness and understanding in such ways is healthy or even feasible, but I do believe it may be crucial in securing some form of solid peace.

Anyways, I apologize for straying off topic. I suppose what I was aiming to say in the article was that Marissa Johnson doesn’t need to forgive, but that she should work out of a place separate from her anger. Perhaps the concepts of anger and grievance are too intertwined for this to be possible. I was suggesting in the article that the members of the Bernie Sanders crowd also should not have responded to Johnson from a place of anger, but it would be a lie to say that their grievances related to the occurrence are anywhere near the grievances she holds, the grievances which moved her to make this speech. The standards to which this country holds African Americans and many other People of Color are far more rigid than the standards to which this country holds White Americans. My hope someday is that all individuals are held to these high moral standards. Perhaps that is overly simplistic and unfair. I have only spent a few years grappling with such topics (and only have within the bubble of my whiteness) so I can only assume it is overly simplistic. I hope this response in some way makes sense and thank you so much for sharing your perspective.

Johnson claimed in an interview with the above commenter and another person, that Sanders and his supporters were violent. She said it more than once. However angry they were, or are, that’s not a license to lie. Also, there are so many other people they could have ambushed like this, who were more deserving. I can’t help but wonder who influenced this action.