By now we know that online school has been hard for students who have stayed isolated in their households, but what about the people on the other side of the screen? Teachers have been talking to blank screens for over a year now – and it has had an impact.

The Roosevelt News conducted a survey in April, interviewing seven teachers to see how the last year has been for them personally. When asked how stressed teachers were on a scale from one to ten, ten being the most stressed and one being the least, four teachers reported being over a five. Drew Tocco, Roosevelt’s marketing and advertising teacher, says that “working at home means that I am essentially living at work,” and that he feels more pressure to be productive, leading to more stress when he’s not actively working.

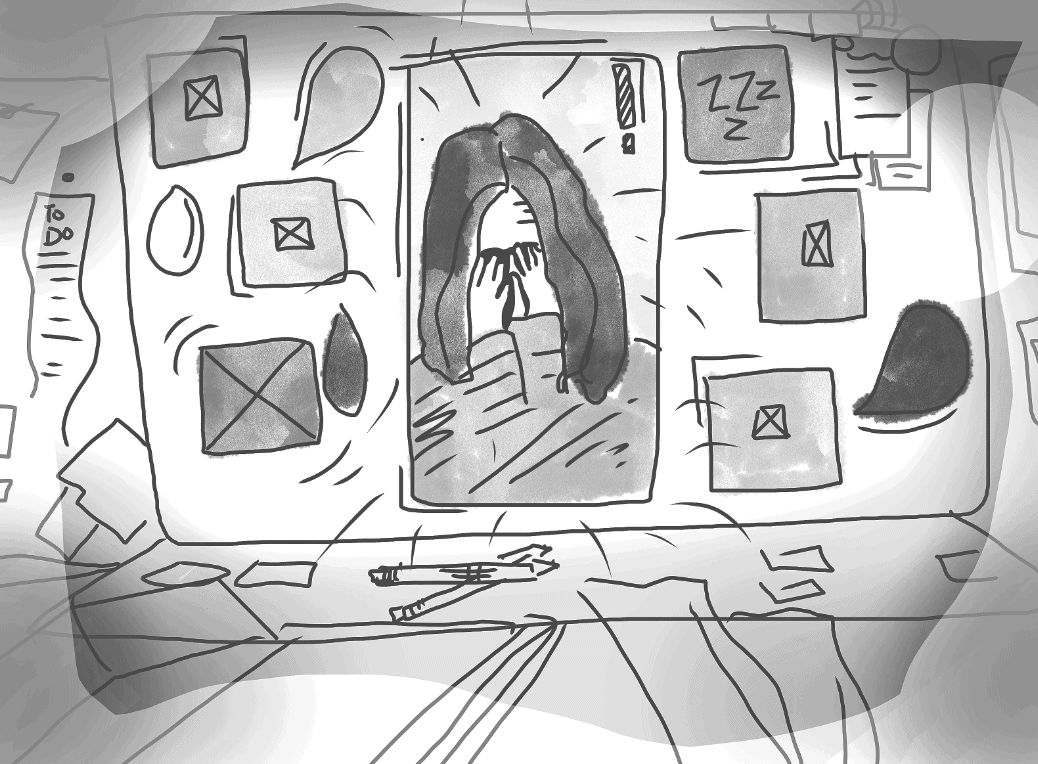

Several teachers reported feeling that their work-to-life balance was off. Like many people who have been working from home over the last year, teachers wake up already in their workplace. Because there’s no clear separation between work and regular life, Tocco says that he and his fellow colleagues often find themselves working from early in the morning to late at night.

Barbara Burton, a Roosevelt social studies teacher, describes how the work of planning, preparing, grading, and meeting with students never feels finished. Many teachers feel that they are putting in more work to create a healthy learning environment, but the lack of effort from students to turn on their cameras or participate in class makes it hard for teachers to tell if the content is even reaching their students.

Additionally, teachers are unable to fit in all of the material that would be taught in a usual school year. Some Roosevelt teachers felt that because they could not adequately teach the length and depth of their courses, they don’t even know if the work they are putting in is making a difference in their students’ lives.

“Most of us are educators because we want to interact and make an impact with students,” Burton says. “We are currently working hard without any sense of whether it matters to the people we are doing it for.” There can be a lack of reward for the work teachers are putting in when they are not seeing as much participation and feedback. Judson Miller, a Roosevelt math teacher, describes it as a “relational vacuum.”

Tracy Landboe, a Roosevelt science teacher, says, “At times I would end a class — the silence and lack of energy was deafening and it should not be that way with high schoolers.”

When asked if their students’ lack of participation has affected teachers, Tocco states that “teaching is like performing.” He tries his best to “smile and be happy in order to pump people up … but in-person when I do that … you get that feedback, you get something back in it.” He goes on to say that he puts “…a lot of energy in, but [online] you just get little to nothing back, so it can be really draining.”

The year has left teachers with new stressors; one being the mental state of their students. Tocco says he struggles to find a balance between worrying about his students’ “mental well-being and academic well-being” and his own mental health. He feels he needs to remind himself that there is only so much he can do. “It’s my responsibility to give them the resources and help,” he says, “but it’s on students to take charge of their own stuff.”

Students may forget that teachers have lives outside of the school environment. That means there are elevated pressures living through this pandemic for teachers outside of teaching online.

Like anyone would be, teachers are scared of catching the virus. Richard Katz, a Roosevelt history teacher, says that he is stressed every time he needs to go shopping for food or gas. Teachers have worried about their parents and families throughout quarantine; many have been secluded from their families who are high-risk, which has only isolated them further.

Landboe says her stress levels increased at the beginning of the pandemic. She was worried about her family, saying, “My parents in their late 70’s were even on a cruise ship!” She says she was dealing with all of this while still teaching online, where she could see “the lack of energy and depression on the few faces of students that would let me see them.”

Despite the different struggles that teachers have been facing throughout the pandemic, some teachers say their stress levels have dropped and their mental health has improved during semester two.

At the beginning of the school year, teachers were working longer hours and were remaking lesson plans from scratch to adapt to the digital realm. Now that Roosevelt has spent a full year in online learning, many teachers have settled into a routine that works better for their mental health. One teacher says that they have adjusted from working 60 to 70 hours per week at the start of the year, to working 45 to 50 hours per week on average.

Tocco affirms that the first semester and second semester have looked vastly different for him. He says that in the first half of the academic year, he was working until 8:00 pm or 9:00 pm every night, as well as eight to ten hours on Sundays. In the second half, he began forcing himself to stop working around four or five in the afternoon and take a break on the weekends. He says that having a better work-life balance has helped him immensely.

Across the board, teachers agree that the pandemic has impacted their mental health over the past year, but they are still pushing forward. Many of them have great support systems, and whether that be family, professional help, or confiding in their fellow coworkers; teachers have prevailed.