The upcoming holiday observes emancipation from enslavement

In June 2021, Gallup found that 60 percent of Americans knew little to absolutely nothing about Juneteenth; it became a federal holiday that same month. For essentially the first time ever, Juneteenth is part of the national mainstream conversation. As a result, the major lack of Juneteenth education in the U.S. has been brought to light. This has sparked dialogues about why, how, and by who the holiday is celebrated.

As Juneteenth approaches, it is important for non-Black members of the Roosevelt community to understand and respect the boundaries that surround its observation.

Juneteenth, sometimes called “Emancipation Day”, is observed annually on June 19, to celebrate the end of American chattel slavery. It is a tradition mostly practiced by Black Americans, particularly in the American south. The specific date of June 19 memorializes the events of June 19, 1865; although Juneteenth broadly commemorates Black resistance to chattel enslavement.

By the 1860s, enslaved communities had already spent over two centuries fighting for their own freedom. Talk of ratifying national emancipation legislation had long circulated in northern white political circles. However, the federal government stalled on passing anti-slavery laws and prioritized diffusing tensions with the South, where chattel slavery was prevalent.

Eventually, the conflict reached a tipping point, and the American Civil War began in 1861.

Throughout the war, President Lincoln was eager to recruit more soldiers to the Union and to establish the power of the federal government over the Confederacy. As a result, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

The Proclamation technically made chattel slavery illegal in every state. However, the Civil War was ongoing at the time, and slaveholders in confederate states simply ignored Lincoln’s executive order.

The Union won the war in April 1865. On June 19, 1865, Union Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Texas to officially instate Union authority over the region. Once again, slaveholders paid no attention to the federal government and continued to illegally practice chattel slavery.

Black abolitionists were not deterred, and their resistance ultimately freed many enslaved Texans. In 1866, formerly enslaved people reclaimed June 19 as a day to commemorate emancipation, and Juneteenth was born. Its popularity dwindled over the years, but a major resurgence occurred during the 1960s and 1970s that spread the tradition across the Black diaspora.

Today, the observance of Juneteenth varies regionally, but the importance of community and shared celebration of Black culture is a constant among many commemorations of the holiday. Large parades and potlucks are often held, and red foods are frequently eaten to symbolize the resilience of those who were enslaved. Some cities and towns crown a ‘Miss Juneteenth.’ Many Miss Juneteenth pageants offer scholarships as a reward for winning the contest, frequently to historically Black colleges.

New York Times reporter Tariro Mzezewa writes in her June 2021 piece “What Does It Mean to Be Crowned ‘Miss Juneteenth’?” that these traditions “involve both the celebration of joy and the commemoration of pain.”

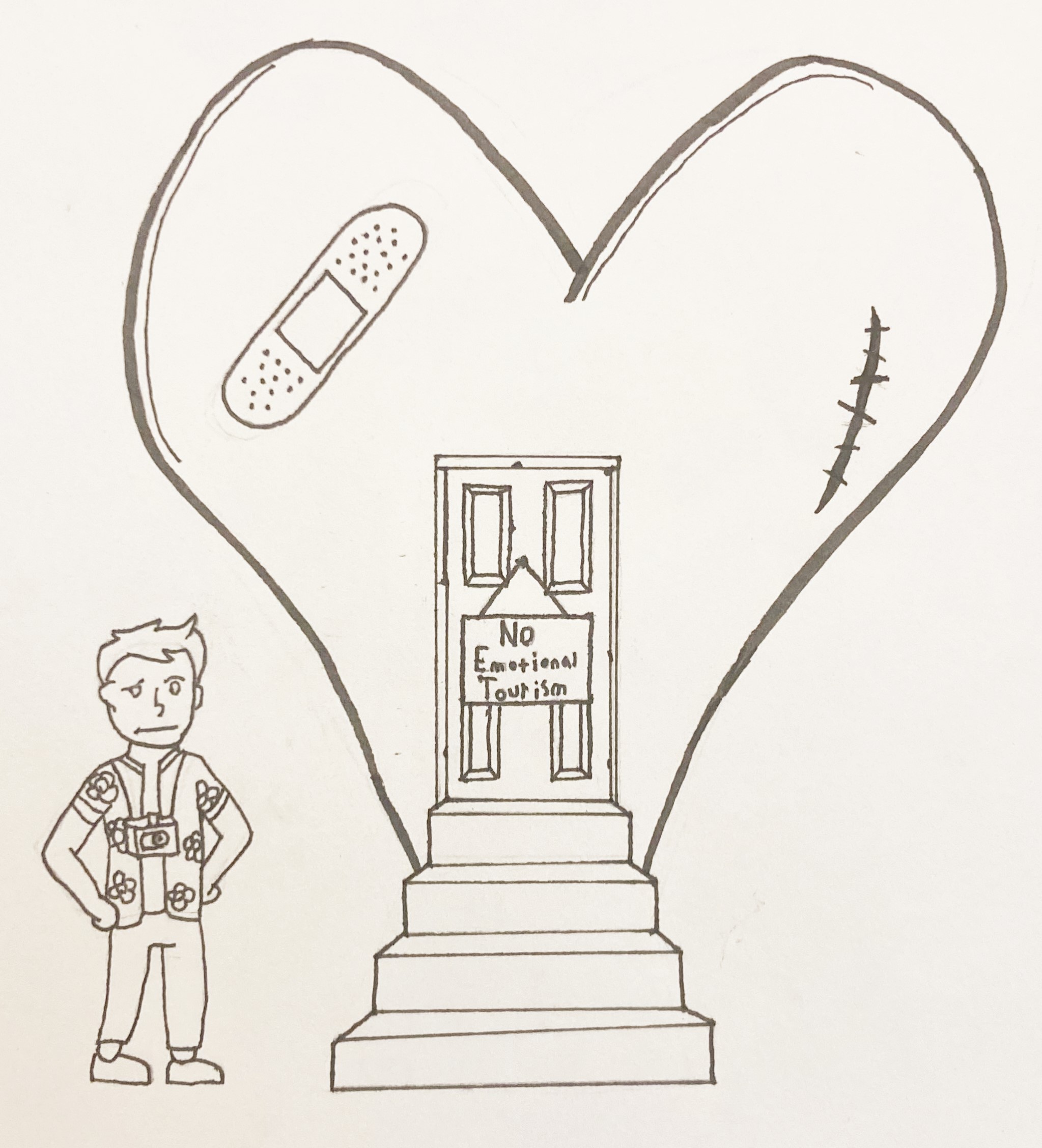

Mzezewa’s comment taps into a larger discussion around Juneteenth. In a broad sense, the national conversation poses the question: when Black joy and pain are being commemorated, is it appropriate for non-Black people to take part in the commemoration?

Journalist Sa’iyda Shabazz says, “Juneteenth is really a holiday for Black Americans. Yes, people of all ethnicities should acknowledge the day, but it’s not a holiday for them to openly celebrate.” Shabazz explains that having the chance to celebrate and converse in a space full of Black perspectives is a significant aspect of Juneteenth.

Junior Jeliyah Sherman, the Co-President of Roosevelt’s Black Student Union, remembers one conversation in particular that she shared with her mother and sister on Juneteenth of 2021: “It was just really nice to openly have a nice family discussion about something that we all experience, and something that’s kind of singular to the African-American community.”

The presence of non-Black people at Juneteenth gatherings can compromise dialogues like the one referenced by Sherman. It can also encroach on a sense of unapologetic Blackness fostered by otherwise all-Black spaces, explains Seattle Times editor Crystal Paul in “When Juneteenth Was Just Ours”, published June 2021.

Paul writes, “[Growing up] Juneteenth was one of the few times of the year I didn’t have to think about the uncomprehending gaze of non-Black people.” She says that it is exhausting to constantly self-police, trying to avoid the ubiquitous and often dangerous possibility of being judged by non-Black people. Juneteenth offers a temporary out.

Paul worries that if Juneteenth enters the American mainstream it will, “be changed from a loud, carefree and Black-as-hell party in the streets to another place where we have to consider non-Black opinions.”

Paul and those who share her perspective were thus conflicted by President Biden’s decision in 2021 to make Juneteenth a federal holiday. On the one hand, national recognition of Juneteenth may prompt important discussions about race. On the other, broadening the holiday’s audience may dilute its significance and decenter Black voices.

Jemar Tisby explains for the Boston Globe: “As people other than Black Americans commemorate Juneteenth, it may lose some of its specific focus on Black people in exchange for a colorblind story of American triumph. Juneteenth was made possible in large part because of the courage and resilience of Black people who persistently fought for their liberation.” Tisby cites the modern observance of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. Discussions on general non-violence and tolerance are popular, while Dr. King’s actual beliefs about race, class, and war go largely overlooked.

Tisby feels that making Juneteenth a federal holiday is a superficial gesture that does little to aid the modern racial justice movement. He says, “The very Republican senators who support making Juneteenth a national holiday simultaneously oppose critical race theory and the 1619 Project, which seek to expose the roots of racism in this country.”

In the past, Roosevelt has not officially commemorated Juneteenth. The end of the school year falls two days short of the 19th, so it remains unclear if this year will be the exception.

As for how non-Black members of the Roosevelt community personally choose to celebrate Juneteenth, it’s ultimately most important to listen to Black voices. Paul explains that if non-Black people’s quest for knowledge overrides the comfort of Black celebrators, then the point has been lost.

She says, “It’s true that Black history is American history. So, here’s hoping Juneteenth can become a holiday that we observe as a country, a holiday to reckon with our past, but also a holiday where Black folk get a dang break.”