In recent years, students and staff alike have voiced concerns about the lack of diversity in class curricula at Roosevelt High School. While the establishment of courses like ethnic studies is seen by some as a fundamental step in fostering a more antiracist and inclusive environment, many believe there is still room for improvement.

Currently, Roosevelt offers a variety of language arts courses to upperclassmen that concentrate on multiculturalism — the notion that everyone’s cultures and personal identities, especially those of marginalized groups, deserve to be heard and reflected in their community — and diversity, such as African American Literature and Margins and Centers.

Ethnic studies is another class that focuses on multiculturalism and diversity, in addition to topics of personal identity and resistance, and is offered as a social studies credit. Jordana Hoyt, an ethnic studies teacher at Roosevelt, says her priorities for the course center around “the idea of bias, and being open about bias, and trying to integrate more identities.”

What is critical race theory?

Critical race theory (CRT) is a core concept of the ethnic studies curriculum that has been at the center of public discourse over the last year, and has been particularly contentious in public education.

Despite its seemingly recent emergence, CRT was established over 40 years ago by several Black American legal scholars, including Alan Freeman, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Richard Delgado, and Cheryl Harris among others, as a social movement and conceptual framework for legal analysis.

Since then, it has expanded and been applied to various fields including education, communication, and sociology. According to The New York Times, CRT “argues that historical patterns of racism are ingrained in law and other modern institutions, and that the legacies of slavery, segregation and Jim Crow still create an uneven playing field for Black people.”

Polling data from The Economist and YouGov reveals that most Americans are unfamiliar with the principle of CRT. In fact, 64% of Americans self-report knowing at least “a little” about CRT, while the rest claim no knowledge of the subject. Of that 64%, a majority claim that racism is not a systemic problem – despite evidence to the contrary.

In 2019, the Federal Reserve Board found that the median Black family’s wealth is less than 15% of the median white family’s. According to The Sentencing Project, Black Americans are incarcerated at almost five times the rate of white Americans. Adherents of CRT assert that these disparities aren’t due to inherent racial differences, but rather, are the effects of historical and systemic racism.

Hoyt understands there are many misconceptions about divisive educational concepts like CRT. She says some believe that “Critical race theory means that we’re only being critical of the United States.”

Instead, Hoyt argues that theories like CRT embrace certain aspects of U.S. history, such as freedom and democracy, while simultaneously critiquing other aspects, such as the systemic legacy of racism, and how to overcome inequities that persist today.

Additionally, many critics see CRT as “unpatriotic,” and that it undermines the anti-discrimination progress of the civil rights movement. According to the Washington Policy Center, CRT teaches that “White students are ‘oppressors’ guilty of implicit racism’ and that their fellow students of other ethnicities are ‘oppressed,’ regardless of their true experiences.”

Kimberlé Crenshaw, a legal professor and leading proponent of CRT, contrasts this idea, stating in an interview with CNN: “Critical race theory just says, let’s pay attention to what has happened in this country, and how what has happened in this country is continuing to create differential outcomes.” She continues, “So, critical race theory is not anti-patriotic. In fact, it is more patriotic than those who are opposed to it because we believe in the 13th and the 14th and the 15th Amendment, we believe in the promises of equality. And we know we can’t get there if we can’t confront and talk honestly about inequality.”

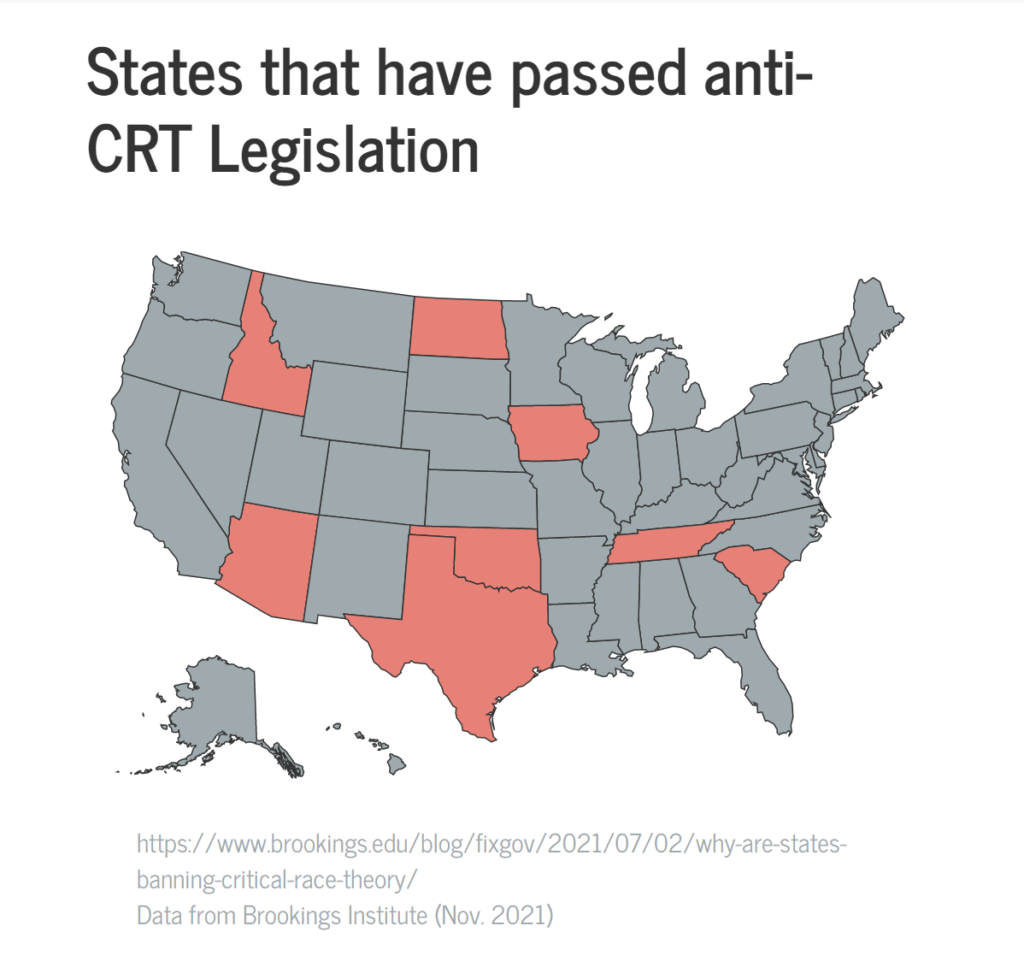

These varying beliefs about CRT have led many states to place restrictions on incorporating aspects of the concept, as well as diversity and antiracist curricula, in public schools.

In May, Montana Attorney General Austin Knudsen issued a binding opinion that CRT is racially discriminatory, because it treats “individuals differently on the basis of race” and “creates a racially hostile environment.”

According to the Brookings Institute, in the past year, nine states have passed anti-CRT legislation. An additional 20 states have introduced similar plans or legislation, with several local school boards following suit.

Reframing the narrative

Part of expanding the breadth of curriculum at Roosevelt beyond ethnic studies could involve incorporating topics from sources outside traditional curriculum producers like the College Board — the administrator and developer of the Advanced Placement (AP) program.

According to The Atlantic, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement is currently developing a curriculum of its own — one that centers the 13 core principles of the movement relating to intersectionality, restorative justice, and compassion, and incorporates them into all classes, year-round.

Additionally, many academic coalitions have recently attempted to reframe the way Americans think about their country’s history. New York Times reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones’ “1619 Project” is an ongoing initiative that aims to place the “consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the very center of our national narrative,” and examine the implications this history has in contemporary life. Hannah-Jones offers a collection of published essays, poetry, a podcast, and course materials and lessons.

The project was met with a lot of initial positive reaction, receiving the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Commentary and being celebrated for its comprehensive scholarship of Black culture, history and influence in a society that has traditionally minimized perspectives and contributions of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC).

The project, however, has also faced criticism from liberal and conservatives regarding its lack of historical nuance. In a letter to The New York Times, a dozen Founding and Civil War era historians expressed concern, “The 1619 Project offers a historically-limited view of slavery. […] The breadth of 400 years and 300 million people cannot be compressed into single-size interpretations.” The letter would go on to say, “The 1619 Project asserts that every aspect of American life has only one lens for viewing, that of slavery and its fall-out.”

A year after the 1619 Project was published, the Trump administration announced the now dissolved 1776 Commision, a “pro-American curriculum” in response to the “twisted web of lies” currently being taught in U.S. public schools. The former president said the commission would “encourage our educators to teach our children about the miracle of American history and make plans to honor the 250th anniversary of our founding.”

The commission quickly received criticism from historians and academics including official condemnation by the American Historical Association (AHA) and 47 other historical organizations for its idealism and oversimplification of the past and failure to incorporate perspectives of BIPOC. “The authors [of the 1776 report] call for a form of government indoctrination of American students,” the AHA council states, “and in the process elevate ignorance about the past to a civic virtue […] that relies on falsehoods, inaccuracies, omissions, and misleading statements.”

CRT, the BLM curriculum, the 1619 Project, and other similar academic movements highlight the systemic inequality and structural racism in the U.S., attempting to shift the narrative to a more diverse one in contrast to the traditional, and encourage more empathy and understanding.

Yet specifically teaching through these curricula is not necessarily a requirement for fostering a safer and more diverse school culture. Rachel Heilman, a history teacher at Issaquah High School, says in reference to new branded theories and syllabi, “I definitely consume them myself, so I know what’s in them, […] but then I work them into the bigger tapestry of my course.”

In Heilman’s opinion, “We need multiple lenses, not just one lens.” She advocates that educators should be aware of these new theories and curricula, and implement aspects of them into their own curricula.

Ethnic studies puts the concept of multiculturalism at its forefront. Holding open discussions, promoting self-reflection, and empowering students to share their identity and experiences with their peers are all examples of how to integrate multiculturalism into the classroom.

America has long prided itself in being ‘one nation.’ But, Heilman argues, “How can you be one nation if you don’t even know what that means?” It’s impossible to be a single community unless every member within that community is given adequate visibility.

Data from Brookings Institute (Nov. 2021)

Mandating ethnic studies

Despite the importance of ethnic studies for employing concepts like multiculturalism, many students opt to take AP U.S. History (APUSH) — the other social studies course option for juniors.

To some, getting rid of APUSH altogether might seem like an easy way to increase ethnic studies registration. However, support for AP courses is strong. “That’s a big bureaucracy that involves teachers all over the country. And then it’s also a corporation,” says Heilman. AP courses are designed by The College Board, a national organization that holds much power in the education sector.

Daniel Gross, Social Studies Department Head and APUSH teacher at Roosevelt explains, “It would take more than an individual to change the actual curriculum. It would take a large systemic movement.” Individual educators or district-level coalitions effecting nation-wide change isn’t a realistic scenario. However, there are still alternatives.

Since 2019, the Seattle Public Schools has required three credits of social studies to graduate. Within this credit list, civics, world history, and geography are obligatory sub-categories of social studies that students must explore, while ethnic studies is an optional sub-category. However, there is a fourth year of credits that could serve as an ethnic studies course requirement.

Gross suggests, “There could be a standalone ethnic studies class in ninth and tenth grade in place of a world history section or AP Human Geography.” If the course became available for underclassmen, students could graduate high school having taken both ethnic studies and APUSH.

According to NPR, the APUSH curriculum was previously re-structured in 2006, in 2014, and re-updated again in 2015 in response to largely conservative criticism. “I bet that they’re gearing up to review it,” Heilman speculates.

Diversity beyond social studies

Looking beyond social studies, there are many opportunities for schools to incorporate diversity and multiculturalism.

However daunting it may seem to educators and the district, the theme of multiculturalism could easily be placed at the forefront of many Roosevelt courses beyond social studies. For example, the school could teach a unit in biology that decentralizes the white male body, which has long since been the primary subject of the science world.

Similarly, Roosevelt could offer a jazz program that examines the roots of jazz in Black culture. A section in an algebra class that talks about the subject’s origins in the Middle East could help students contextualize what they are learning.

Heilman, with a background in history and South Asian studies, has been working to design a specialized course that focuses on South Asian history. She describes it as “a geography class, a history class, and a sociology class, all mixed in together.”

Here, Heilman models one method of incorporating multiculturalism and diversity into other classes by designing new courses centered around those principles. According to Heilman, however, designing courses requires a lot of time and curriculum-building expertise, of which some educators have neither.

For teachers simply trying to integrate multiculturalism into their current classes, Rebecca Mark, Ph.D. and Associate Professor of English at Tulane University, suggests that educators move away from the traditional top-down model of teaching, to encourage more open discussion between students, and bring in experienced speakers.

In spite of setbacks, such as the 1776 commission, proponents of ethnic studies and other similar courses around the country continue to advocate for the development of racially equitable and critical coursework.