As March came and went, the one event at the forefront of students’ minds was next year’s budget. Well, not quite. In reality, many students do not know that Roosevelt’s 11-member Budget Committee meets several times in early spring to propose a budget to the Building Leadership Team, or BLT.

While the budget allocation process is rarely met with excitement by students or teachers, the process is a significant one. On the surface, the budget plays a role in determining the operational, day-to-day realities of the following year. Deeper than that, the budget is a moment of reflection for Roosevelt to ask: What are our values, what is our shared vision, and what systems do we have in place to make that happen?

Changes for the 2021-22 school year

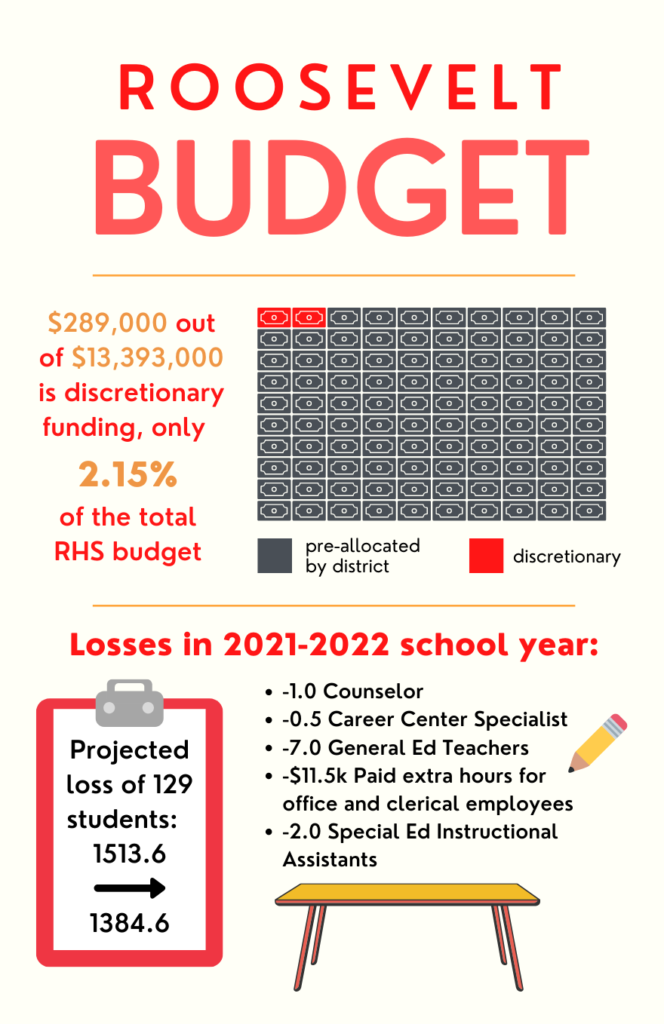

With low predicted enrollment for the 2021-2022 school year, serious budget cuts were inevitable. As Language Arts teacher Edmund Trangen puts it, “In a budget year like this, there are no good choices.” Seven full-time certified teaching positions will be lost next year due to the drop in enrollment projected by Seattle Public Schools.

Most budget decisions are made at the district level. Roosevelt’s total budget this year is $13,682,000, but just over 2%, or $289,890, is left for the RHS Budget Committee’s discretionary spending.

Language Arts teacher and BLT member Amy Noji says that because the district has cut these positions, it “means that your newest and youngest, least experienced, but could possibly be rock stars teachers are displaced.” This is because of the district’s seniority-based layoff system, which is a product of the Seattle Education Association’s bargaining process with SPS. As Noji says, this laying off of new teachers “happens over and over and over again.”

The BLT diverted half of the discretionary funding to funding teachers in an attempt to reduce this loss, funding an additional 1.1 full-time teacher.

This decision was a change from the Budget Committee’s original proposal, which had directed that funding towards keeping the fifth counselor position and the Career Center Specialist position.

While the BLT’s budget passed the staff vote, not all staff members are in support of the decision. Counselor Carrie Richard says that “we kept the Academic Intervention Specialists, who have a very targeted focus. So they work with very specific small groups of students and they have a great impact, but it’s very specific. The career center specialists and counselors work with all students. And so I felt like the broadest reach got reduced.”

Roosevelt, like any other high school in the district, is allocated a certain amount of additional funding to support students who do Running Start. Next year’s budget diverts those Running Start funds towards reducing teacher loss. Richard says that using the Running Start money for general teachers rather than counseling to support Running Start students goes against historical practice. “For a school with so many Running Start students, it’s pretty disturbing to me that that money is not going back into the people that work with the students.”

Richard adds that “I would have been fine if they had used the running start money on the Career Center Specialist, I would have been completely fine with that … fact that they did both and they used Running Start dollars to do it … I’m having a very hard time with that … I don’t think it’s student-centric.”

Richard is not the only staff member disappointed over the loss of the Career Center Specialist position. Jason Schuler, a Paraprofessional Special Education Instructional Assistant, BLT member, and Budget Committee member says that the Career Center Specialist impacts a lot of students not just at Roosevelt, but in other school buildings as well. “This person no longer has a position through the district, and that is huge. We want to prepare students not just for college, but for leaving high school, being out there as a young adult. So I think that is going to be our biggest impact … we’ll feel that one.”

Everyone agrees that the current person in the Career Center Specialist position, Edward Rho, does an exceptional job. Richard says that “he does the most amazing newsletters and workshops and invitations and fairs … yes, he’s supporting FAFSA and things like that, but he’s also talking about all these other opportunities that are out there.”

Using a data-driven approach in budget decisions

While there is disagreement over next year’s decisions, there is also staff concern over the budget process in itself.

Trangen was the one Budget Committee member to abstain in the vote recommending the budget to the BLT. In the Budget Committee meetings, Trangen says he asked questions like, “Do we have information on the demographics that are served by this position? Do we have information on the effectiveness of this or that position as an intervention? Do we have information that is desegregated racially?” Trangen says, “Those questions were just not answered.”

One system that could provide data in decision making processes like these is called a Multi-Tiered Systems of Support, or MTSS. MTSS is a problem-solving framework that uses research to provide support and interventions that work for all students. A key component of MTSS is its data-driven approach.

Trangen says that “If you have a functioning MTSS system, what you can say is that ‘based on our universal screening … we determine that such-and-such percent of kids had this academic gap. We employed this intervention … for x percent of kids they saw this type of growth, the other group didn’t.’”

Having that data accessible in the budget allocation process could bring transparency around why certain positions were kept over others, rather than relying on anecdotal evidence which can be clouded by internalized biases.

However, right now, Trangen says that “We don’t have those structures in place.” While there is some guidance around practices that should be used for all students, according to Trangen, other interventions for smaller groups of students “happen but not in the systematized way that you can track.”

While data could improve the decision making process, the MTSS, like any tool, is not an all-encompassing solution. “The MTSS stuff is a way to have that conversation, it doesn’t solve all the problems, and in fact what you’re going to find when you do that kind of assessment is that there are racial disparities in the gaps that you see and if the MTSS work isn’t done with an anti-racist approach, then it becomes another oppressive tool,” says Trangen.

Another reality for the MTSS system is that not everything important can be quantified. Noji says that it can be difficult for staff to turn what they do into numbers. “How do you quantify motivation?” She asks. “When you help a kid to … feel that they are seen and their perspective is valid and maybe you helped them to realize that they’re smart because they haven’t felt smart because of the system that does tend to beat down some of us? How do you quantify that? What’s real success?”

A system to track the effectiveness of different supports would not be a simple fix, but it could be a step forward in bringing clarity to the budget allocation process.

Bringing anti-racism into the budget process

Part of becoming an anti-racist institution means bringing anti-racism into the budget process. “There is an old saying, a budget is a statement of values. I think that in order to live out our values as an anti-racist institution, the budget has to be a point of clarity about that,” says Trangen.

Trangen continues, “There are things you can do in terms of investment and reallocation that will counter some of the institutional and structural racism that is a part of Seattle Public Schools and a part of Roosevelt in the way that it persists over history.”

One part of countering structural racism is addressing the disproportionately low number of BIPOC staff compared to BIPOC students. According to Crosscut, in Seattle during the 2018-2019 school year, BIPOC students made up 53% of the student population, while 81% of teachers were white.

The reason for this disparity traces back to the aftermath of the Brown v. Board decision in 1954. When many classrooms were integrated, Black students often moved to schools that had been for white students while schools that had Black students only closed. The result: tens of thousands of Black teachers and staff were fired.

Now, BIPOC staff face other obstacles. The retention rate for BIPOC staff is lower than white staff. Nationally, 19% of BIPOC teachers leave or move schools, compared to 15% of white teachers, according to the Learning Policy Institute.

According to a 2018 Minneapolis Public Schools report, some reasons for this decreased retention rate include repeated racist interactions with other staff, racial isolation – i.e. being one of the only teachers of color in a building, and feelings of job insecurity.

The Black Lives Matter in Schools Movement has adopted “hire more Black teachers” as one of their demands, for clear reasons.

Having teachers of color in the classroom affects students of color in several ways, including but not limited to boosting overall academic performance, improving test scores, improving graduation rates, and increasing aspirations to attend college, according to a study by the Learning Policy Institute. An American Educational Research Association study also found students are more likely to be placed in gifted programs when taught by teachers of their same race. For white students, being taught by BIPOC teachers can reduce racial stereotypes and implicit biases. In short, it is important students of all races see BIPOC role models.

Noji also notes that teachers of color often are the ones to push for change in an institution. “Overwhelmingly… BIPOC staff, teachers, are doing a lot of work. A lot of work to make shifts happen… And it’s a different way that we do the work. We do the work, but like when we experienced pushback, it’s not just pushback on an issue that we care about. It’s pushback that’s personal.”

While the need to retain BIPOC teachers is clear, there are places where the budget process clashes with retaining BIPOC teachers.

Budget Committee members are often reminded that they are dealing with “positions not people.” On one hand, the “positions not people” framework can help reduce the discomfort that comes when making decisions about people’s jobs. On the other hand, it could also keep important conversations from happening.

“One of the top demands of the Black Lives Matter at School movement … is to hire more Black teachers [and] hire more BIPOC teachers,” says Noji. “And you know that a Black teacher is going to be cut and we can’t talk about that?”

This traces back to a larger district policy, driven by union concerns and demands. Seattle Public Schools has a seniority-based layoff system, meaning that when budget cuts happen, the last hired is the first fired. This means that when a tough budget year rolls around, the Roosevelt administration has no say over who gets laid off, which makes intentionally retaining teachers of color hard.

Critics of the “last in first out” (LIFO) methodology think the layoff policy should instead focus on maintaining a diverse faculty and keeping the best staff.

Supporters of the seniority-based system say that there is no better alternative. Developing a system that truly identifies the “best” teachers is easier said than done — quality-based factors, such as student surveys and principal input, can have biases. Supporters say seniority at least offers some objectivity.

Despite this, the current seniority-based policy makes it hard to intentionally retain BIPOC teachers. “But yet that’s what the movement is asking for, and it makes a whole lot of sense. Our students are asking for that,” says Noji.

At the same time, changing teacher layoff policy is just one part of effectively retaining BIPOC teachers. Diversifying the teaching force expands beyond the budget process and into addressing the racist interactions and work environment BIPOC teachers face. As Trangen says, when it comes to facing structural racism in our schooling system, “A budget is a way into some of that, but it is only one of the ways in.”

The future of Budget Committee:

Many on the Budget Committee agree that the current system is not working. Richard says that it is the Budget Committee’s “proposal moving forward is that there not be a Budget Committee and that the BLT do this.”

Under the current system, the Budget Committee meets intensively for several weeks, coming up with a proposal to bring to the Building Leadership Team. This year, the BLT rejected that proposal. Richard says that when the BLT rejected the proposed budget, “that gave them like two days to come up with something different. And they didn’t have all the previous conversations.”

Even if the BLT determines the budget in the future, it still proves difficult for staff to make decisions that could impact their own positions.

Noji says, “It got really, really uncomfortable when we had to start looking at individuals and … they feel attacked about their work that they’re doing or what they’re not doing or how effective they are.”

No matter how many reminders that they are dealing with “positions not people,” the decisions can still feel personal. Richard says that “There’s a lot of personal emotion … I get very emotional and worked up about things … And it’s hard to remove all that.”

What everyone in the budget process can agree on is that more representation – of students and families, particularly BIPOC students and families – is needed.

Trangen says that he’d “love to see more outreach to students of color to be a part of the budget process.” He continues, saying that “We do a lot of guessing about what students are experiencing … When we have students speak directly to us in a decision making space it is extremely powerful.”

In the BLT, there has been work to create a survey for BIPOC families to better know where the problems are in Roosevelt as an institution. A survey could help inform future budget reallocations.

Schuler, who is on the BLT, says “It would be great if [a survey] happened not just once a year but many times through a year so we could get a better understanding of how our culture is in general. Everybody that comes into that building should feel … safe to be here, … and I think a lot of our students of color don’t sometimes.”

“Our school has a lot of work to do when it comes to outreach and engagement with families of color, creating welcoming spaces for families of color,” says Trangen. “In this case, literally a seat at the table.”