In the summer of 2020, alongside the rest of the United States, Roosevelt found itself confronting persistent racism in the school community, with instances of racial harassment on both social media and school grounds being reported to administration.

But even before those specific incidents, conversations about bringing in a racial equity consultant were occuring within building leadership. In August 2020, the LaJuana Johnson Leadership & Development Group (LJLDG) was hired.

The LaJuana Johnson Leadership & Development Group

LJLDG is a consulting business that encourages change within workplace communities. They offer training of staff volunteers, evaluate environments through an equity lens, and provide school climate assessments.

LaJuana Johnson, founder of LJLDG, shared her experience and knowledge as Roosevelt’s Race and Equity Facilitator.

“What I like to say is we maximize people potential,” says Johnson, when asked to describe the company’s goals and purposes. “And that’s based on helping individuals and […] organizations develop in their competency around […] racial equity and anti-racism, but also leadership […] And then, I like to sort of focus on what I call the trifecta, which is personal, professional, and organizational. So how all those work together.”

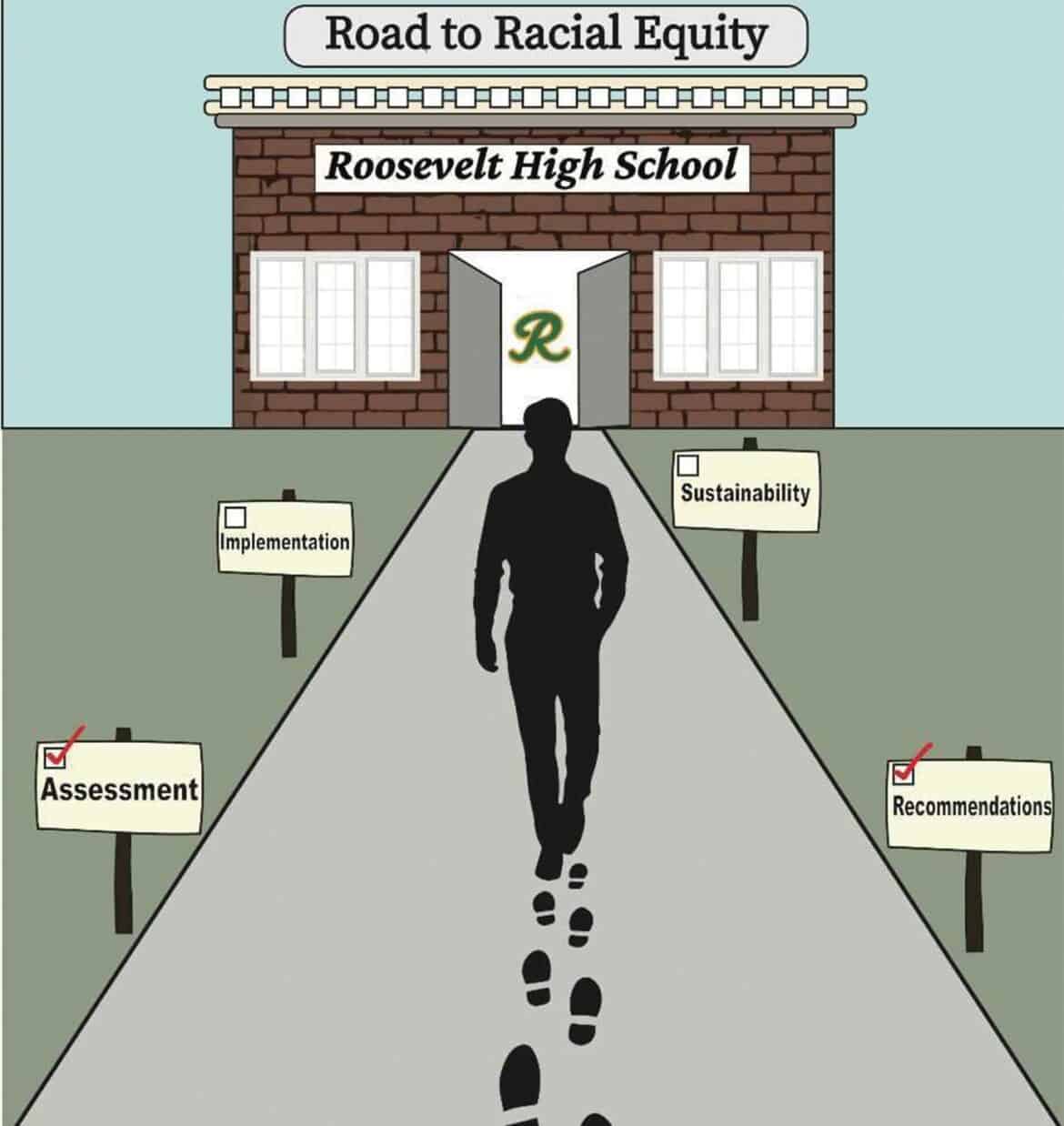

The engagement contemplated a 3-year plan for addressing race and racism within Roosevelt culture, including assessment, recommendation and implementation phases.

Amy Noji, Language Arts teacher and member of the Teacher Leadership Cadre, a group of teacher volunteers who lead staff in professional development, goes on to summarize Johnson’s contribution in terms of the heart, the head, and the hands: “Helping us to impact other human beings in terms of developing empathy and an understanding of the heart. Then helping us to understand things on an intellectual level, you know, the head. And lastly, how does it impact practice […] in the way we develop programs […] what are the things that we’ve always done here that need to be looked at again?”

LJLDG synthesized their first year of work in a report, formally titled, “The Roosevelt High School Racial Equity Assessment.” This report was distributed to Roosevelt students and staff by email on Nov. 19, and to families on Nov. 22.

With the release of the report, Principal HkwauaQueJol Hollins shared the Zoom link to a Race and Equity Report Town Hall Presentation on the evening of Nov. 22. This call debriefed the report’s findings and featured a student panel.

Purpose and Approach

The LJLDG report seeks to answer three questions:

- “To what extent is RHS a racially equitable and positive environment for all school community members?”

- “To what extent is RHS a racially equitable and positive environment for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) students, staff, and families?”

- “What is needed, wanted and envisioned for a racially equitable, safe, and positive environment?”

LJLDG’s work with Roosevelt has been a catalyst for most of the changes taking place in the school this past year.

Johnson played a critical role in holding spaces for training sessions on leading conversations about race and equity; these were offered to staff, teachers, alumni, PTSA, and students.

“We were basically asked […] how we racially identified, and then we got to be in groups where we could talk with folks who identified racially in the same way,” says Jordana Hoyt, a teacher in the Social Studies Department, and co-chair of the Building Leadership Team (BLT).

Hoyt continues, “To have more sort of open conversation and […] for our staff of color to feel like they had a true space that was theirs, and didn’t feel like they had to educate anyone […] I found it extraordinarily informative, raw, honest, in a way I don’t think I had experienced facilitated conversations about race ever before.”

In the Town Hall Presentation, these meetings were described by Hoyt as resulting in the development of authentic connections, and an active shift toward viewing the Roosevelt community with an equity and equity literacy lens, as opposed to focusing on the achievement gap.

The Racial Equity Report defines the achievement gap as a measurement based on test scores. This method of measurement places indirect blame on students of marginalized groups, due to a selective showcasing of data.

Typically, the data exhibits that marginalized groups score lower than their peers, and fails to provide a reason for that trend. The Racial Equity Report goes on to explain that this stems from a lack of school system support and resources for BIPOC students.

Educational inequities such as “less qualified teachers, low expectations of students of color and low-income students, and a less rigorous curriculum,” are all examples of this, relays the Racial Equity Report.

Microaggressions, skewed disciplinary measures, and everyday challenges— such as disparities in health care and nutrition access— reinforce an already challenging educational atmosphere, continues the Racial Equity Report.

Successes found within Roosevelt

The findings section of LJLDG’s report begins by acknowledging some early successes Roosevelt has had in managing racial equity work. According to the report, “An awareness of the problem exists, and energy is being directed towards racial equity work and cultivating a safe and welcoming environment.”

Statistics provided support this claim. Survey results pulled from 41% of Roosevelt’s student population show that 92% of students want to learn more and do something about racism at school. Moreover, 73% feel there is something they can do about racism at school, and 85% agree racism is a problem in the Roosevelt community.

Areas for Improvement in Roosevelt

The second and longer section of the findings, “Opportunities for Growth,” details areas in which the school community needs to improve. The primary points made relate to strengthening leadership and communication around these issues.

Shifting cultural climate from toxic white supremacy to a safe, welcoming, and supportive environment is high priority, says the report.

Within the staff and student body, actions to create a safe and welcoming space for minorities are vital. Continuing conversations, developing skills to handle microaggressions, and increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of reporting procedures would contribute to the creation of those spaces.

“This is where we start talking about our keys to being successful, and how we’re going to achieve them,” relays Roosevelt’s Principal, HkwauaQueJol Hollins. “This is where we start talking about our core values. This is where we start defining what we mean by certain systems, and properties, and things that are being put into place.”

The report goes on to emphasize that in order to implement these changes successfully, a systems-level approach is needed. Other necessary requirements include engaging the entire school in conversation, and upholding strong commitment to racial equity work.

“We have a movement happening at Roosevelt, but the movement is only effective if we’re working together. We have a common vision, we have a common understanding, we create strategies and a plan,” explains Noji.

Other necessities include avoiding racial equity strategies lacking in action, or ‘equity detours,’ as they’re called in the Racial Equity Assessment.

Strategies that combat equity detours could look like establishing clear boundaries and consequences for racist behavior, and instituting a curriculum that teaches about oppression, identity, and the history of communities of color— specifically those represented in the RHS community.

When asked about future steps, and ensuring sustainable change, Hollins explains that “It’s focusing on defining our fundamentals […] everything should lead back to student achievement.”

“Moving forward, we’re going to have a better, more well-rounded student,” Hollins elaborates. “We’re going to have somebody that can contribute a lot more to not only the working world, but the world. I think that’s our ultimate goal […] I want you to become better than us. I want to give you my heart, my soul, my lung, to become better than us […] And so with that, we can only move forward with our equity and diversity work.”

LJLDG’s Three Step Plan

LJLDG’s original engagement was intended to last three years, pending review at the end of each year. Funding for year one was provided in part by the Roosevelt Foundation, a group of alumni, staff, parents and neighbors that provide financial support for academics and enrichment activities.

BLT and the Foundation are currently discussing funding for year two, to support implementation of the report’s recommendations. “What we’re trying to do is we’re working toward sustainability. We’re working toward creating policies, practices, and procedures, and systems that […] advance racial equity, that transform the school cultures,” explains Johnson, in regards to the three step plan.

The first step typically starts with an assessment. Information regarding the environment of the “entity”— the business or school— is collected through interviews, focus groups, listening sessions, whatever it is that works best.

The second step consists of implementation. Establishing a framework that best suits the “entity”— in Roosevelt’s case, a large, urban, majority white high school.

Student input is also essential during this process, adds Johnson. “That’s a big […] part of that implementation phase, is involving all the voices of the stakeholders and creating a path forward together,” she says.

The final step is ensuring sustainability. Much like the rest of the three-step plan, it contains many smaller steps condensed into larger ones. These steps include coordinating student voices, remaining aware of staff overburdenment, and preserving a sense of urgency.

With that in mind, it’s especially important to consider the incorporation of the district, and how it plays into public school requirements. Regulations set by the district may be aligned with Roosevelt, but they may also not be, Johnson explains.

In addition, though the district has its own racial equity plans and initiatives, they move at a slower pace than public schools.

“Maintenance […] anywhere short of the three to five years out, is about sustainability,” Johnson finishes. “How do we make sure that we can create policies, practices and procedures to sustain the work? […] Cause that’s where the change needs to happen […] to make sure the work continues.”