Like many Roosevelt students last year, I watched with stunned disbelief and anticipation as a tidal wave of posts from RHS student protesters hit social media during the walkout. Their journey to the UW was documented every step of the way: there were tweets from outsiders watching the action, as well as students calling for their peers to join them. “No justice. No peace. No racist police”, the protesters chanted. This November marks the one-year anniversary of these protests, and of the Ferguson grand jury decision not to press charges against the cop who shot Michael Brown. Once again, protests have broken out in Missouri that have the Roosevelt halls buzzing. But this time, they went far beyond simple marches through the streets.

At the University of Missouri, in Columbia, celebrations broke out amongst teachers and staff after President Timothy Wolfe and Chancellor Richard Loftin announced their resignation on Monday, November 9. This had been a much-anticipated event for students, who condemned the leaders’ neglect of racial issues on campus and spurred protests, which originated on social media and marched their way onto the quad. Concerned Student 1950, an activist group formed to fight against racism at the university, led assembled students in a moving rendition of “We Shall Overcome” in homage to the Civil Rights Movement. Their adaptation of Pete Seeger’s famous anthem to a more modern time emphasized the fact that though the Civil Rights Movement is a thing of the past, the battle against racism and discrimination continues to endure. However, though the campaign was inspiring, the protesters went a bit too far to carry out their message.

Since his appointment in 2012, Wolfe’s tenure as president has been fraught with controversy and public discontent. More recently, students and staff protested his seeming disregard to demonstrations of racism at the University of Missouri, or “Mizzou”, and his inability to open up an inclusive dialogue on the topic. On September 12, the president of the student body, Payton Head, called for student awareness of racism at the university. Following a recent incident, he claimed that racial slurs hurled at him while at campus threatened his sense of safety and needed to be addressed. To their credit, Head’s classmates responded with solidarity amidst further demoralizing incidents of racism at Mizzou. Eventually, their social media campaigns evolved into full-fledged protests. Even then, the president and chancellor continued to ignore students’ concerns throughout the past few months, resulting in more extreme action on the protester’s behalf.

“It’s necessary for students to engage in political activism.”

On November 2, following the drawing of a swastika on the wall of a campus bathroom, graduate student Jonathan Butler announced his decision to embark on a hunger strike, ending only with Wolfe’s termination as University of Missouri president or his own death. This action shocked Butler’s friends and fellow students, resulting in continued protests and threats by the football team to boycott practices and games until Wolfe was either fired or resigned. Though Butler’s hunger strike and the subsequent fallout were arguably the greatest contributing factors to Wolfe’s and Loftin’s resignations, Butler’s proclamation was nothing if not extreme. A student should not have to feel as though the only way to create progress is through death threats. Sure, hunger strikes are valuable during major political movements against a greater government, but to resort to such a measure against one solitary institution is quite another matter.

The students’ fears for their friend were thankfully ended on November 9, when Wolfe resigned and Loftin promised to demote himself to a less influential position, thus ending Butler’s strike. That same day, protesters clashed with photographer Tim Tai, a senior at Mizzou, who was working on a freelance project for ESPN. Tai was detained by protestors and unable to reach the tents, while the students and some staff members chanted “Hey hey, ho ho, reporters have got to go”. Tai refused to leave, insisting that he had First Amendment rights to document the proceedings, just as the First Amendment promised the freedom of speech to the protesters who detained him. This right was ignored; the crowd insisted that they had the right “to move forward”, and pushed him further away from the tents. Yet again, crowd actions were driven past heroism and into madness when mob mentality took the place of rationality.

Butler’s hunger strike and the treatment of Tai by Mizzou protesters reflect a political stance driven more by emotion than common sense. These actions, though not unsuccessful, detracted from the overall message of the campaign, making the protesters appear more self-righteous than heroic.

Black students are typically suspended or expelled three times as much as white students

In this day and age, it’s necessary for students to engage in political activism. It doesn’t only pertain to racism, spanning to women’s rights, rape culture, and more. In their march against the tolerance of racism, students at the University of Missouri spoke out in a meaningful and persuasive way. Hopefully, their actions will spur other college students to follow in their footsteps. High school students, too, are affected by sexual harassment and racism. According to the American Association of University Women, in a 2011 survey, 58% of 7th-12th graders said that they had experienced sexual assault. Racism, unlike sexual assault, is an institutional as well as a societal problem in American Public Schools. Black students are typically suspended or expelled three times as much as white students, and more diverse high schools are often saddled with less-experienced teachers, according to the U.S. Education Department’s 2011-2012 Civil Rights Data Collection. Looking at these statistics, it’s plain that we, as high school students, have most likely already confronted these issues or will confront them in the years to come.

Along with the rising significance of student activism across America comes a necessity to approach this process rationally and safely, without threatening students or staff. As we open up a discussion of these issues on college and high school campuses, we must also keep the discussion open: not only to students’ social media forums, but also to the press, so that student discussions can be turned into an international dialogue. Already, student protests in Mizzou are being cross-examined by news platforms across the states, only one year after Ferguson protests made their way into Seattle and into the New York Times. As issues surrounding rape and racism continue in American schooling, the magnifying glass closes in on student responses. All eyes are on us.

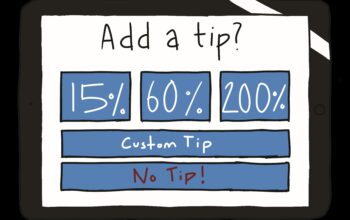

Featured Photo: Many students are quick to take strong stances when it comes to social justice issues, but how do they express these stances? Photo by Ruby Hale