The pressures to succeed in academia start early, but at what cost?

Between March and April, high school seniors anticipate a letter that will decide their future. Nail-biting, sitting around the computer, they wait for college decisions to start rolling in.

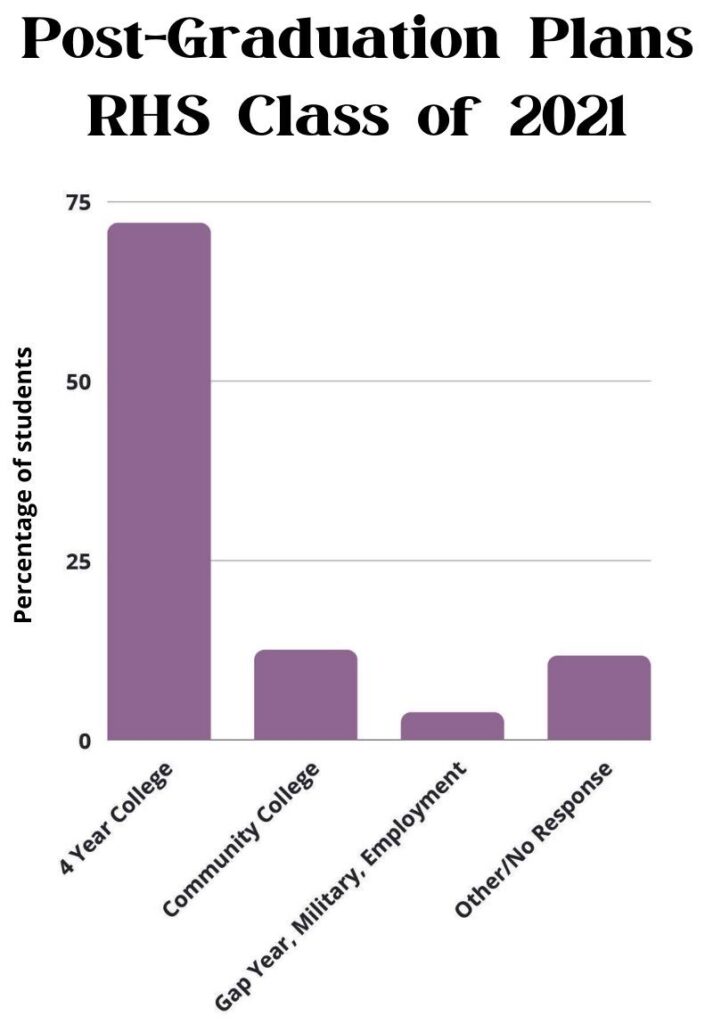

Today it seems like almost all students at Roosevelt High School are going to university; over 90% of 43 responses to a survey by The Roosevelt News confirm this trend.

In recent decades, higher education, paired with the culture that surrounds it, has been increasingly prioritized by students. Influences for this perceived ladder to success often come from peers, parents, and teachers. “I don’t feel any pressure to go to college, but since most people do, I just feel like I should,” says an anonymous student survey respondent.

The TRN survey also found that 70% of Roosevelt students report feeling pressured to pursue higher education. However, this emphasis on higher education has brought struggles with social and school-life balance for many — all while studies and trends have shown a decreased value of the high school diploma.

In the pursuit of reaching a subjectively defined ‘good’ university, many students fall into workaholic tendencies associated with hustle culture — “An addiction to work, a pathology, a behavior pattern that persists across multiple organizational settings.” The American Psychological Association also defines the syndrome as being “comprised of high drive, high work involvement and low work enjoyment.”

Workaholism results in many students having a work-life balance that’s difficult to manage; the TRN survey found that overall, students report feelings of guilt and distress when they are not being productive.

Workaholism has found its place among students in part due to the pressures of getting into university. The TRN survey found that 74.5% of students report a score of seven or higher out of 10 when asked to rate the pressure they feel to pursue higher education.

Beginning freshman year, students attempt to polish their college applications by participating in activities that make them stand out in applicant pools of thousands of other students. This often means adding on to their workload beyond the seven-hour school day.

According to U.S News, the AP participation rate at Roosevelt is 67%, while nationwide, it’s 38.3%. Roosevelt’s high percentage of university-minded students correlates with the significant percentage of students taking AP courses.

Roosevelt Counselor Courtney Judkins notes, “I see through my experience here at Roosevelt that a lot of kids stress with taking the highest level classes and then stress themselves out here at a high school level. It actually makes me worry when they go into college next year, if they [will be] able to handle that extra stress or pressure.”

According to the Roosevelt High School website, 72% of the Class of 2021 planned to attend a four-year college directly after graduation, and 12.5% had plans for community college. An additional 3.8% of students planned a gap year to pursue the military or employment. Roosevelt is also ranked 13th in college readiness in the state, according to U.S. News.

At Roosevelt, it seems the established standard for most students is to attend college. This begs the question: How did college degrees become so prized, and how does this affect the long-term outcomes of students?

A Step into the Past

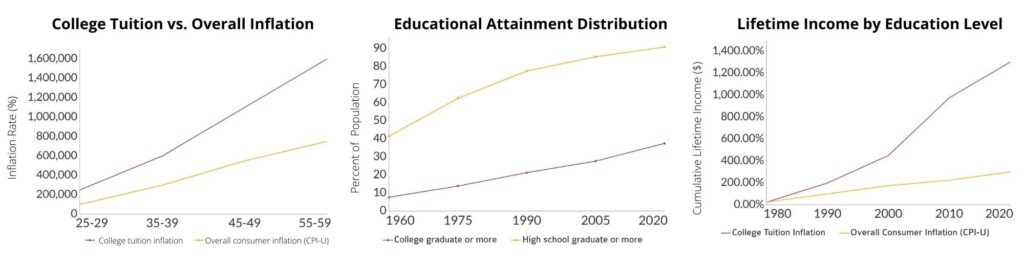

Financially, the value of high school education has dropped since the 1960s. As reported by data from the Pew Research Center, between 1965 and 2013, the average high school graduate’s earnings decreased by more than $3,000, from an average yearly salary of $31,384 to $28,000 (after adjusting for inflation).

This decrease in the value of a high school diploma can further explain why many students feel obligated to pursue a post-high school education. In fact, American Millennials (born between 1981-1996) are the most educated generation in history.

According to the Pew Research Center, more than one-third of Millennials have at least a bachelor’s degree. In contrast, in 1965, only 13% of 25 to 32-year-olds had a college degree, with the percentage popping up to 24% in the 1970s and ‘80s.

On the flip side, Millennial college graduates earn about $17,500 more than their high school graduate counterparts.

Historically, college degrees have become more desirable to employers — data by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reveals this trend. The overall share of those with only a high school diploma in the workforce is declining, while those with college degrees are increasingly becoming more prevalent.

“Degree inflation” is revealed by data collected by Harvard Business School in 2017. Researchers compared the percentage of current employees who possess a degree, to the percentage of job postings requesting a bachelor’s degree or higher.

The data found that 16% of employees held a degree, while 67% of job postings in their field requested a degree, leaving a 51% “degree gap.” According to Ellucian, 62% of students surveyed said they are currently attending college to improve their job prospects.

In 1992, those with high school diplomas made up 36% of the labor force while those with a bachelor’s degree were 18%. In 2016, the high school diploma percentage dropped to 26% while the bachelor’s increased to 24%.

The Return on Investment of Higher Education

However, there are concerns about this mindset, Judkins says, “A lot of people believe that if they’re furthering their education, it’s like guaranteed money. But unfortunately, it’s not always the case.” Her concern plays out for the 25% of college graduates who make less than the typical high school graduate, according to the New York Fed.

Overall, tuition and fees for university have increased. Data collected by U.S. News shows how over the last two decades, tuition and fees have increased by 144% at private universities, 165% for out-of-state public universities, and 212% for in-state public universities. During this time, inflation rose by 50%.

According to Forbes, the increase in university costs is due to increased spending of administrators, overbuilding of campus amenities, higher dependence on high-wage labor, and easier access to student loans.

A 2020 study by IBM found that a third of graduates regret pursuing higher education because of how much it costs. A survey by U.S. News found that the average student loan debt for the class of 2020 was $29,927, a 20% increase from the class of 2010. Today, the nation’s total student debt stands at $1.3 trillion.

The cost of four-year colleges and universities may also discourage students from attending. ECMC Group found that the likelihood of attending a four-year school had sunk more than 20% since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The number one cause for the decrease in likeliness is student loan debt.

However, the attention a degree receives is undeniable; those who only obtain a high school degree have a three and a half times higher chance of falling under the poverty line compared to those with a bachelor’s degree.

Under Pressure and Under Stress

Workaholic tendencies can be a byproduct of pressure. TRN found that 23 out of the 38 survey respondents attribute their pressure to attend college to family. Meanwhile, 20 students also mentioned general social pressures, and 10 included self-inflicted pressures.

The pressure of succeeding and continuing academia beyond K-12 also lies in the school environment. Roosevelt has a relatively high graduation rate, in fact, the second-highest in SPS.

“[At Roosevelt], there’s a very strong college-going culture — 90% of our graduates go to college, both community college and university,” says Ron Stuart, a counselor at Roosevelt. “That’s pretty impressive for a public school. But also here, there is a lot of pressure to go to what’s a ‘good school,’ … there’s that pressure to make an announcement.”

Stuart continues to discuss the value of big-name universities that comes from peers, “[The school has] to be somewhere flashy, somewhat big time. I’ve heard a lot of kids … presenting their school to their friends. And having that questioned, being like, ‘Is that even a good school?’ Kind of crushing, [right]?”

The Burdens of Work

The standard at Roosevelt to attend four-year colleges correlates with the workaholic tendencies seen among the student body. The TRN survey found that 76.7% feel “guilty” when they’re not productive, and 16.3% say they feel “somewhat guilty.” In the same survey, 74.4% of students report a nearly constant feeling of being “not productive enough.”

These pressures and feelings of guilt can manifest themselves through negative mental health outcomes. According to a study by Oxford University, 50% of high school students self-identify as stressed or anxious, and 25% of them attribute these symptoms to schoolwork.

The National PTA and National Education Association recommend limiting homework to 10 minutes per night per grade level. However, according to the Statistic Brain Research Institute, American teens report an average of three or more hours of homework each night.

One Stanford research report finds that excess schoolwork is “counter productive,” resulting in “stress, physical [and] mental health problems and a lack of balance.”

Finding a Good Fit

This need to be productive at Roosevelt may be, in part, due to its high achieving standards. “The pressure to go to a university is pretty universal, but I think it’s more noticeable due to so many students being college-bound. So I think you see more students being caught up in that at Roosevelt,” says Stuart.

A common mindset at Roosevelt seems to be that four-year college is the only option after high school. “College, yes, is important, but it’s not the only thing out there,” says Judkins. “It just really depends on what a student really wants to do in the future and what career they’re choosing that they will be happy with for the next 50 plus years.”

However, when asked if students are adequately educated in alternative options after high school, 25 out of 33 TRN survey respondents said they were not. One student respondent says, “Not really, I don’t hear many people talking about options other than going to a university.” Another replies, “Nope. Should I be?”

Judkins addresses that the counseling department has shifted. “I don’t think it’s emphasized as much as it could be. I know us as a counseling department have tried to kind of step away from all the college stuff and try to explore the other options a little more.” She continues, “The only thing that I think is so unfortunate for us is that we don’t have enough of those students taking advantage [of those resources].”

Furthermore, Stuart mentions the pressures to maintain high grades, “I think there’s a lot of pressure to get A’s.There’s so much grade inflation in high school … that colleges aren’t really looking at grades anymore as much as the quality of classes and extracurriculars. … Colleges are asking: ‘Did you challenge yourself at high school?’”

However, Stuart also warns students against overworking themselves, “When colleges are telling us two or three [APs] a year is probably way more than you need — and we get kids taking five AP classes — … that’s not necessary. … It’s a very competitive environment which can cause lots of anxiety and stress.”

“What we tell kids is to find a good fit,” Stuart shares. “It’s [college], not like a prize that you win.”