“Helloooooo Green and Gold”- Principal HkwauaQueJol Hollins

The new head of the school has taken to addressing the student body as “Green and Gold” rather than the traditional “Rough Riders.” This has left students and faculty wondering if it has anything to do with Theodore Roosevelt or the Rough Riders’ racist history and if it is time to examine the mascot, and school namesake, a little more carefully.

Many upperclassmen and staff are accustomed to using ‘Riders’ to address students, which is why school clubs use the name too (e.g. ‘Rider Cheer’). Often, in the hustle and bustle of life at school, it’s easy to forget the history of day-to-day vocabulary. Still, when people use words rooted in white supremacy and racism, it communicates that these systems of oppression are acceptable.

The same courtesy must be applied to the school mascot. As a community, Roosevelt claims to be inclusive and embrace diverse backgrounds. When it comes to marginalized members feeling heard and seen, racist names are a blatant obstruction. How can students be expected to think this school strives to be anti-racist when Theodore Roosevelt was notoriously anti-Indigenous and racist himself?

According to History Link, the school was named after President Theodore Roosevelt in 1920 and adopted the nickname ‘Rough Riders’ shortly thereafter. If the school name needs changing, it is only fair that the mascot follows suit.

Roosevelt was second-in-command of the Rough Riders— a ragtag group of individuals that made up the First Volunteer Cavalry of the Spanish-American War. Separate from Roosevelt, the Rough Riders participated in racism and perpetuated colonialism.

Roosevelt included Native Americans in his regiment. In his book, The Rough Riders, Roosevelt praised the full-blooded Pawnee member, William Pollock, for being educated at “one of those admirable Indian schools.” In the same breath he also explained that the Native Americans were “shaded off until they were absolutely indistinguishable from their white comrades,” referencing how the majority of them were mixed race.

Even in his most progressive strides, like being the first president to invite a Black man to the White House, Roosevelt believed in racial hierarchy and meritocracy. His ideals deeply shaped his interactions with non-white people, demonstrating the belief that they were racially inferior but could climb the ranks. If non-white people did not appear to be contributing something valuable to society, he had no interest in them.

In many respects, Roosevelt was quite progressive. He implemented stronger government regulation of big business, and set aside 2 million acres of land for national forests, reserves, and wildlife refuges. At the same time, he “favored the removal of many Native Americans from their ancestral territories, including approximately 86 million acres of tribal land,” according to History.com.

When it comes to Theodore Roosevelt, and any historical figure, there must be an acknowledgement of nuance. There will never be a perfect idol. Theodore Roosevelt was deeply human, and as such, deeply flawed. Perhaps some of these faults could be accepted, if it weren’t for the direct harm they are causing students and staff today.

Françoise Musafiri, a Roosevelt senior, shares valuable insight into what it’s like to be Black at Roosevelt. Referencing Theodore Roosevelt’s problematic history, she says, “Why didn’t they take that into consideration while making the name? […] I’m very much a second thought at the school.”

Musafiri suggests taking surveys of Black and Brown students, and allowing their opinions and perspectives on the school’s namesake and mascot to be heard, as their voices have been dismissed in the past.

Other schools with racist mascots have also stressed the importance of seeking community input. New York City’s Nyack Public Schools district took over a decade transitioning their mascot from ‘Indians’ to ‘RedHawks.’ The process involved a student-led committee dedicated to selecting a mascot that honors equity and inclusion, elicits pride, and involves student input.

It is important that this process does not feel rushed. Musafiri says, “I think even with what happened summer of 2020, it was like, we want results, we want results now… instead of sitting down and being like, what do the students want?” Referencing the events of the particular summer, Musafiri touches on the student body’s urge to see immediate action from the administration when harmful and inappropriate events are reported. A name change is worth the patience and the investment necessary to do it right.

Some have suggested Eleanor Roosevelt as the new namesake for the school, but this feels too easy. Proper effort must be employed in order for it to be worthwhile for students of color.

Additionally, it would be good to consider a name to reconcile this racist past. Selecting a prominent person of color to represent the school would certainly not fix all the issues, but it would be a start.

For example, Ralphe Bunche Elementary School honors the first African American awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. A former student reported that she and fellow students of color felt safer and more secure in their identities in school environments when surrounded by images and symbols of Black excellence. And, they reported experiencing a true sense of pride.

School spirit has always been an important part of the Roosevelt culture. It helps ASR President, Madi Mulick, get out of bed and feel excited to come to school. Renaming the school may bring forth concerns about its present day history and student pride. Change can be scary, but sometimes that’s what makes it necessary.

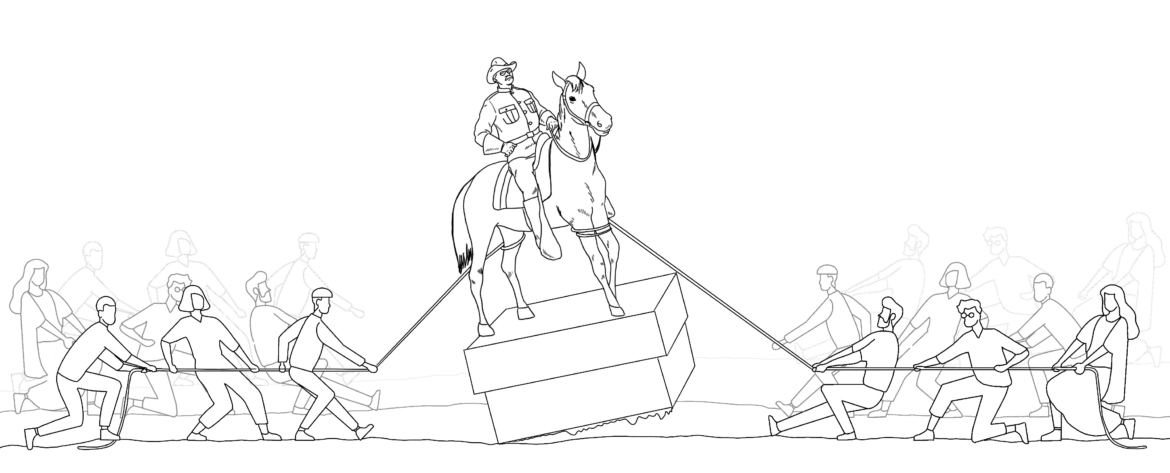

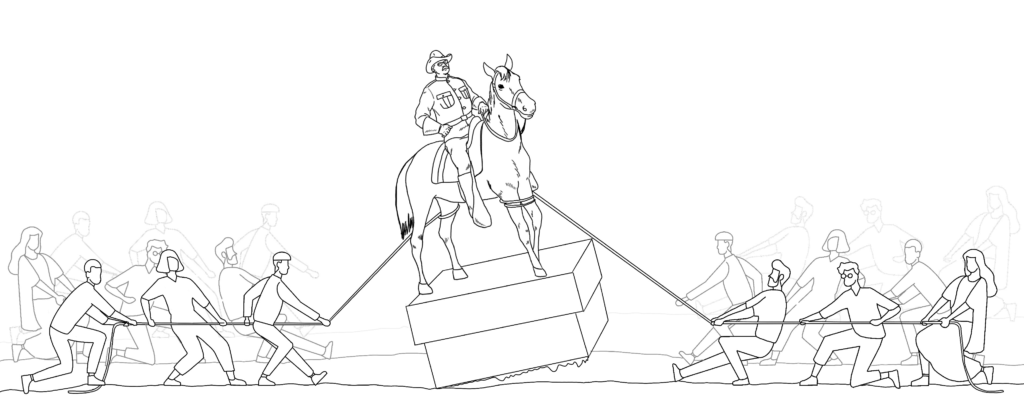

Those in opposition argue that renaming the school erases history. They say that people will forget Theodore Roosevelt and his accomplishments if the school is renamed. However, renaming the school doesn’t mean he vanishes from the history textbooks, it simply means the school will no longer put him on a pedestal.

Similar critics will argue that if every historical figure were held to today’s moral standards, none of them would be admired. Nevertheless, it is only natural that a school reevaluates its public representation every fifty years or so. Schools deserve the opportunity to reflect justice, and if the community’s standard of justice changes in years to come, so should the school. Ultimately, the change doesn’t have to happen today, tomorrow, or even this year. Regardless, the efforts should start immediately. Students and staff should talk to one another and make it abundantly clear that there is no giving up until students of color are made a priority at Roosevelt.