Southern states take to censorship of racial and LGBTQ+ topics

Illustrations done by Iva Ekemcic and Isaac Belina

Ethnic studies curriculum has been a contentious topic of national focus since students at San Francisco State University first began protesting the lack of representation in course offerings in 1968. This strike was the first of its kind, led by Asian-American, Latino-American, African-American, and Native American students. It eventually gave way to the nation’s first ethnic studies department opening at San Francisco State University, on March 7, 1969.

The past three years have brought this topic back into the often scornful public eye once again, this time focused on K-12 classrooms. Currently, nine states have a mandate that requires ethnic studies classes be available in public schools [accurate?]. In tandem, a debate has broken out over banning certain books that include what several bills in conservative states deem “diverse subjects”, content on the LGBTQ+ community, and discussions of race or racism. Many individuals and officials argue that certain books contain content are age inappropriate for K-12 students, and others argue that books of all topics should be available to children.

Recently, the State of Florida banned AP African American Studies classes from being taught in schools. The Board of Education made a statement that said the class lacked “educational value” and “historical accuracy”. The decision was met with heavy backlash, including from the White House, whose official statement called the choice “incomprehensible.” The Florida Department of Education said that they would be willing to revisit the discussion if they were provided with “lawful and historically accurate content” from the College Board.

The argument that ethnic studies courses are inherently historically inaccurate or opinionated for choosing to highlight a specific group is common in the debate. Proponents of restrictions on this type of curriculum feel that by emphasizing the struggle of one ethnicity, students are left to infer that other ethnicities are responsible or “bad”. Former US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice famously stated on ABC’s daytime talk show “The View” in 2021, “I don’t have to make white kids feel guilty for being white.” . In 2010, Arizona passed the HB 2281 bill, which restricted Mexican American studies in Arizona schools. The bill stated that the program, and ones similar to it, promoted “resentment toward a race or class of people.”

In contrast, many proponents of K-12 ethnic studies curriculum claim that restricting ethnic studies classes is robbing today’s youth of valuable learning. They claim that ethnic studies teaches students about oppression and its effect in past and modern day worlds, as well as encouraging activism and empathy.

Fabiola Torres, a teacher at Glendale Community College says that, “Ethnic Studies ensures that students have an opportunity to develop skills to understand how race, gender, sexuality, and other forms of difference work in the world.”

The discussions of what’s acceptable to teach children have extended beyond the curriculum explicitly shared in the classroom to books available in school libraries. While book bannings are certainly not new, they have become more visible in light of the recent controversy.

Florida has been at the forefront of banning books for years. According to the Harvard Gazette, 40% of book bans in the 2022-2023 school year came from Florida. When asked to “set the record straight” about the “book ban hoax”, Governor of Florida Ron Desantis said, “Exposing the ‘book ban’ hoax is important because it reveals that some are attempting to use our schools for indoctrination.” He continues, “In Florida, pornographic and inappropriate materials …have been snuck into our classrooms and libraries to sexualize our students and violate our state education standards. Florida is the education state and that means providing students with a quality education free from sexualization and harmful materials that are not age appropriate.”

Florida isn’t the only state with a history of book banning. Washington state schools have challenged well known titles such as “To Kill a Mockingbird,” by Harper Lee and “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” By Ken Kesey. Specifically in Washington state, there is criticism against book bans, and many teachers are making the decision to include banned books in their curriculum.

The discussion also extends beyond just topics of race or ethnic history, as Desantis’s comment references. In states such as Florida and Ohio where LGBTQ+ rights and identities are also hot-button issues, books discussing these themes have been deemed by some lawmakers, educators, and parents as inappropriate, “indoctrinating,” and even “pornographic”, as Desantis stated.

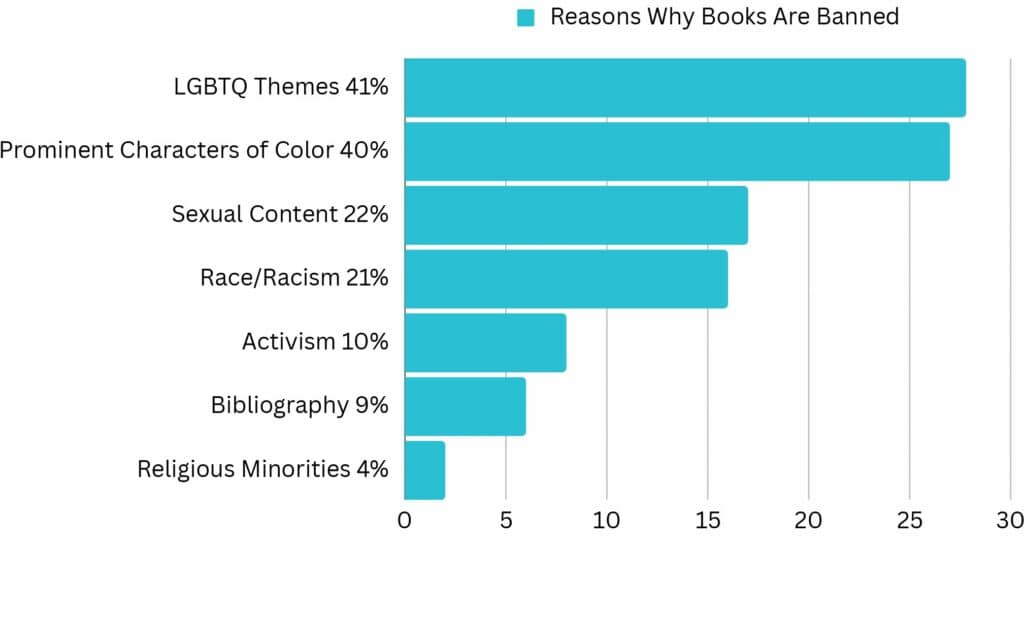

According to PEN America, evidence shows that an overwhelming amount of book bans target LGBTQ+ groups, as well as authors of color.

The Harvard Gazette reported that 45.5% of books put up for debate in the fall semester of 2022 were written by or about LGBTQ+ people. The number one controversial book in the country, with 155 bans, is “Gender Queer” by Maia Kobabe. The book has received much praise for its discussion on identity, but it has also received criticism for perceived sexually explicit content. The book follows Kobabe’s journey from childhood to adulthood while exploring their gender and sexuality, and while the book does contain some sexual content, many believe that it is targeted because of its LGBTQ+ themes.

Numerous individuals argue that children shouldn’t be reading about gender, sexuality, or race while others argue that limiting books deprives children of important learning opportunities.

The First Amendment Museum said that as of the year 2020, 92.5% of books are banned because of sexual content, 61.5% because of offensive language, and 49% because it was believed to be unsuited for a certain age group.

The Seattle Public Schools Ethnic Studies Program Coordinator Alekzandr Wray said, “Ethnic studies are instrumental, I believe, to high school students’ experience. It is at this time of life where a lot of high school students are really coming to understand who they are and what they want for themselves. Ethnic studies provides opportunities for students to explore their personality, to explore what they care about, to explore what their passions are, and to really find their voice and cultivate their voice to uplift it in communities that support student empowerment…read the word, read the world.”

Roosevelt offers ethnic studies courses for grades 10, 11, and 12, and many districts on the West Coast make ethnic studies a graduation requirement.

Stacia Arnoux is a curriculum specialist within the district who assists in the creation of the ethnic studies curriculum. “While I can understand that some people wish to place controls over what material is accessible to or taught to young people because they may find certain parts of history or specific books upsetting or unaligned with a particular worldview,” Ms. Arnoux said, “it is the responsibility of educators and schools to ensure that they continue to teach historical facts from all perspectives and fight censorship of literature in order to continue an objective discourse.”

Many students are making an effort to fight back. There are 50 million K-12 students enrolled in U.S public schools and more than 50% of those students are students of color. While demand for racial justice is higher than ever, students are leading movements from the forefronts, book banning and ethnic studies protests included.