Organizers of Roosevelt’s recent Homecoming Spirit Week drew swift criticism for promoting what some students viewed as a disrespectful and exploitative use of Hawaiian culture, calling out an example of cultural appropriation.

The Associated Students of Roosevelt (ASR) hosted a celebration of school pride in late September. The overarching theme of the spirit week was movies. Monday’s theme? The 2000s Disney film, “Lilo & Stitch,” which is set on the Hawaiian island of Kaua’i.

Within ASR, the designated Spirit Coordinators are responsible for creating the theme of each day of the spirit week. ASR Spirit Coordinator Sophie Ohtake defines the process as a fairly democratic one: students in ASR begin by individually brainstorming spirit week themes before ideas are pooled together and the Spirit Coordinators make the final decision.

As with every ASR event, the spirit week was advertised beforehand. A poster describing the spirit theme of each day of the week was hung in the lower commons, and a video was filmed and edited for ASR’s official Instagram page.

For Monday’s theme, the poster displayed the words “Hawaiian Day.” The video depicted ASR students dressed up in various costumes for each spirit day of the week. For the video’s segment on “Lilo & Stitch” day, ASR leaders wore plastic leis, hula skirts, and mimicked the traditional hula dance.

While the original spirit idea was based on the film, somewhere along the way “Lilo & Stitch” day morphed into “Hawaiian Day.”

Ohtake explains how the original spirit themes were written on the whiteboard and subject to repeated rewriting as the final advertising plan of the Homecoming Spirit Week was produced. In that process, ASR members mistook Monday’s theme as “Hawaiian Day.”

“I think a lot of people associate the beach theme with the Hawaiian theme, like there’s no separation in a lot of people’s minds,” explains Ohtake.

This came out in the form of advertisements for the spirit week which depicted costumes and images that arguably appropriated Hawaiian culture, rather than being related to the movie.

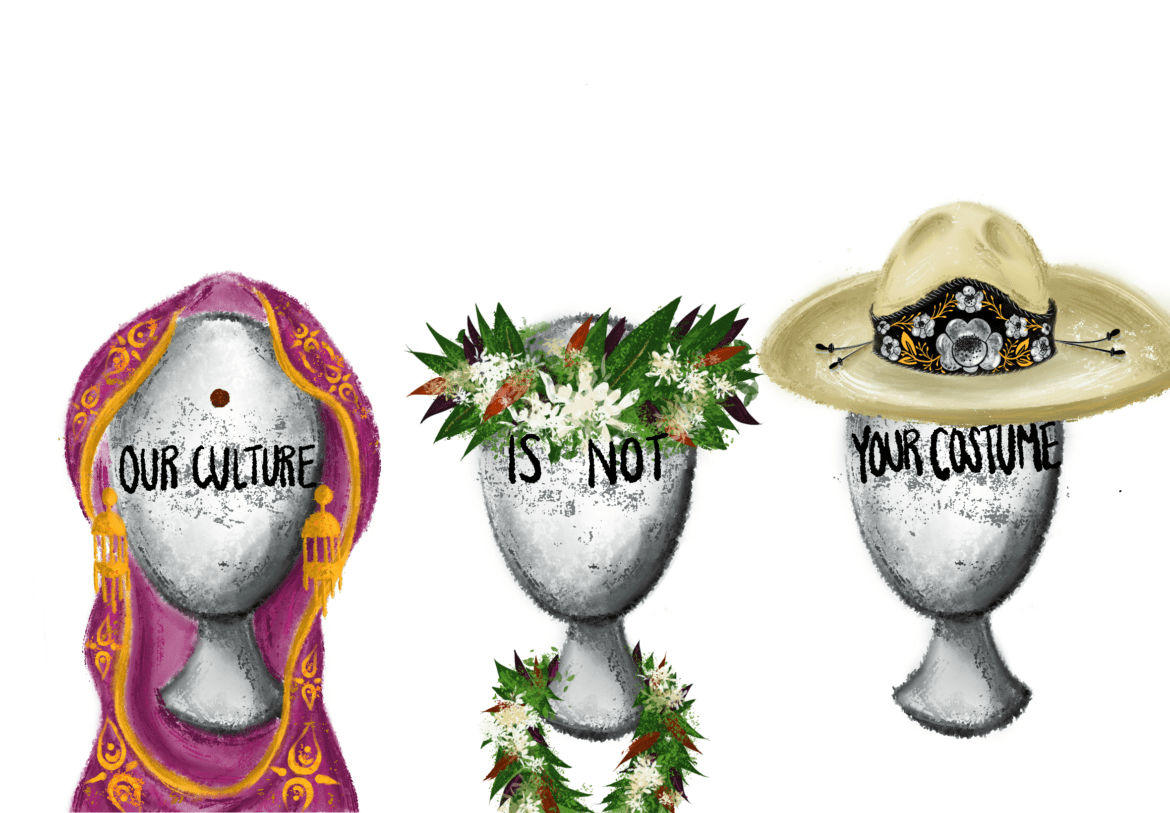

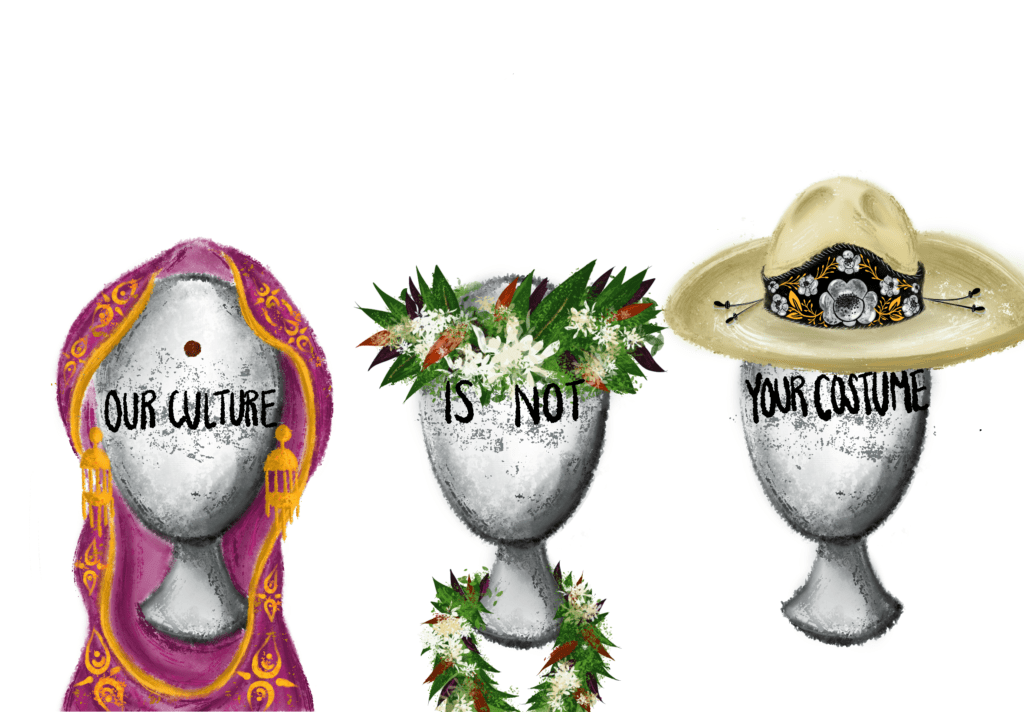

Quite immediately, there was a student response. In the comment section below the Instagram video, a handful of Roosevelt students expressed that they believed the post was appropriating Hawaiian culture. The Cambridge English Dictionary defines cultural appropriation as “the act of taking or using things from a culture that is not your own, especially without showing that you understand or respect this culture.”

Roosevelt junior Henry Burton-Wehmeyer was among the students commenting below the post. He says, “I saw that other people were commenting, which also gave me a little more push.” Burton-Wehmeyer goes on to explain how they wanted ASR to take accountability. “They’re supposed to be the Associated Students of Roosevelt. It didn’t seem very thought out, in a way.”

Roosevelt senior Sera Mills called out the student leaders as well. Recalling the moment, Mills says they were in shock, saying, “after quarantine, I thought we were done with dressing up as other cultures. [ASR] could have even done just Stitch. Like dressing up as aliens, that would have been so fun, so cute. But it had to be Lilo and Stitch.” Mills goes on to explain his frustration with ASR. “It really shows how ignorant our school is, and the stuff we put up with.”

Within a day, ASR had deleted the video from the Instagram page and removed the poster from the Commons. A clarification post was added to Instagram apologizing for the misinterpretation and announcing Monday’s spirit day theme as beach or tropical day, not “Hawaiian Day.”

ASR went on to request that students dress thoughtfully and avoid appropriating Hawaiian culture. Outfit recommendations included clothing along the lines of bright floral shirts and khaki shorts to mimic a tropical vacation.

For some, this amount of action wasn’t satisfying. Mills comments on the follow-up Instagram post in particular, stating, “If you say, ‘We apologize for miscommunication,’ it is like we’re sorry you’re upset. We’re sorry that you interpreted this as being cultural appropriation because it wasn’t, even though Lilo is a Hawaiian girl, and dressing up as a Hawaiian girl is cultural appropriation, that’s what it is.”

Mills continues on to explain the difference between intent vs. impact: it doesn’t necessarily matter if ASR didn’t mean to appropriate another’s culture, because ultimately that’s what happened and amends are necessary.

ASR Secretary Lauren Guise responds to such concerns by saying it was a rushed post. Guise elaborates further, saying, “It was not a perfectly worded statement and the apology portion definitely should’ve been included, but I think it was just more in the moment.”

The ASR website defines the student government’s role as one invested in promoting leadership, initiative, and change in the student body. Debra Jayne Symons, ASR Treasurer, elaborates by saying, “As leaders of the school, people look to us to be examples and lead how the Roosevelt culture should be.”

When figures in the public eye, such as politicians, celebrities, or even student leaders make a mistake, ‘cancelation’ often follows.

On this topic, Burton-Wehmeyer says “I do not think [supporting cancel culture] would be productive. It would create more emotions. Instead of doing that, just own up to your mistake, and move on with your corrected, more learned self.”

In the aftermath of the ASR clarification post to Instagram, Ohtake took it upon herself to research and learn about the long history of Hawaiian cultural appropriation. “I felt like it sucks that the whole [ASR] class just let this go through and not a single one of us stopped to think about it,” she says. “And it’s a mistake that really, I can see a lot of people at the school making.”

Following the event, Ohtake created an infographic of her research and posted it to her personal Instagram story, urging her followers to repost and spread the message. ASR did not repost the material.

Specifically, Ohtake shared an interview with Anne Keala Kelly, a Hawaiian journalist, filmmaker, and activist. In the interview, Kelly discusses the appropriation and commodification of traditional Hawaiian traditions, clothing, and culture.

Ohtake hoped that by sharing this info with the school, the student body would be considerate with their clothing and accessories during Monday’s spirit day celebration. In spite of her efforts in addition to ASR’s quick revision of the promotional materials, some of the Roosevelt population still dressed in traditional Hawaiian clothing, such as leis, for the spirit day.

“I went to school Monday and saw people wearing leis and I was uncomfortable,” says Mills. “I thought that we’d improved and become more aware as a school, and it was proof to me that we hadn’t, and it was kind of disheartening.”

Tourism in Hawai’i was first normalized in the early 20th century. The commodification of Hawaiian culture was quick to follow. The lei is an example of a commodified cultural identifier, traditionally part of Hawaiian celebrational and ceremonial events. “It’s mostly about money now,” says Kelly.

Kelly explains the lack of cultural sensitivity in America, saying, “embedded in every American theft is the denial of that theft, be it theft of land, culture, nationhood, all the things that define a people, all that they need to survive as a people.” Exploiting the cultural identity of Hawaiians is the legacy of this tradition.

Mills speaks to a desire to see more a proactive ASR, saying, “When [ASR has] events like this where they are directly impacting the student body, [they need] to really analyze what they’re about to do and question whether it’s acceptable and, if it’s something that would benefit Roosevelt, as a whole.”

As Halloween celebrations are around the corner, perhaps students will take the event as a lesson for future costumes.