The return to in-person school can be exciting and nerve-racking. With sports, hallway banter, assemblies, spirit weeks, and senior sunrises, students are all being reintroduced to each other’s company. But for others, in-person schooling has meant close proximity to their abusers.

For these students, quarantine was the only way to physically distance themselves from the person who sexually assualted them. An 18-month break from school meant that, with the exception of Zoom calls, students didn’t have to see anyone they didn’t want to.

But the beginning of the 2021-22 school year put this physical distance to a sudden halt as students transitioned to in-person schooling.

Suddenly, students could be forced to be inclose physical proximity to their abuser five days a week, sometimes even in joint classes. One Roosevelt student, who requested anonymity, says, “I’ve been sat next to them. I’ve been partnered with them on group projects. I’ve been forced to email back and forth with them for projects.”

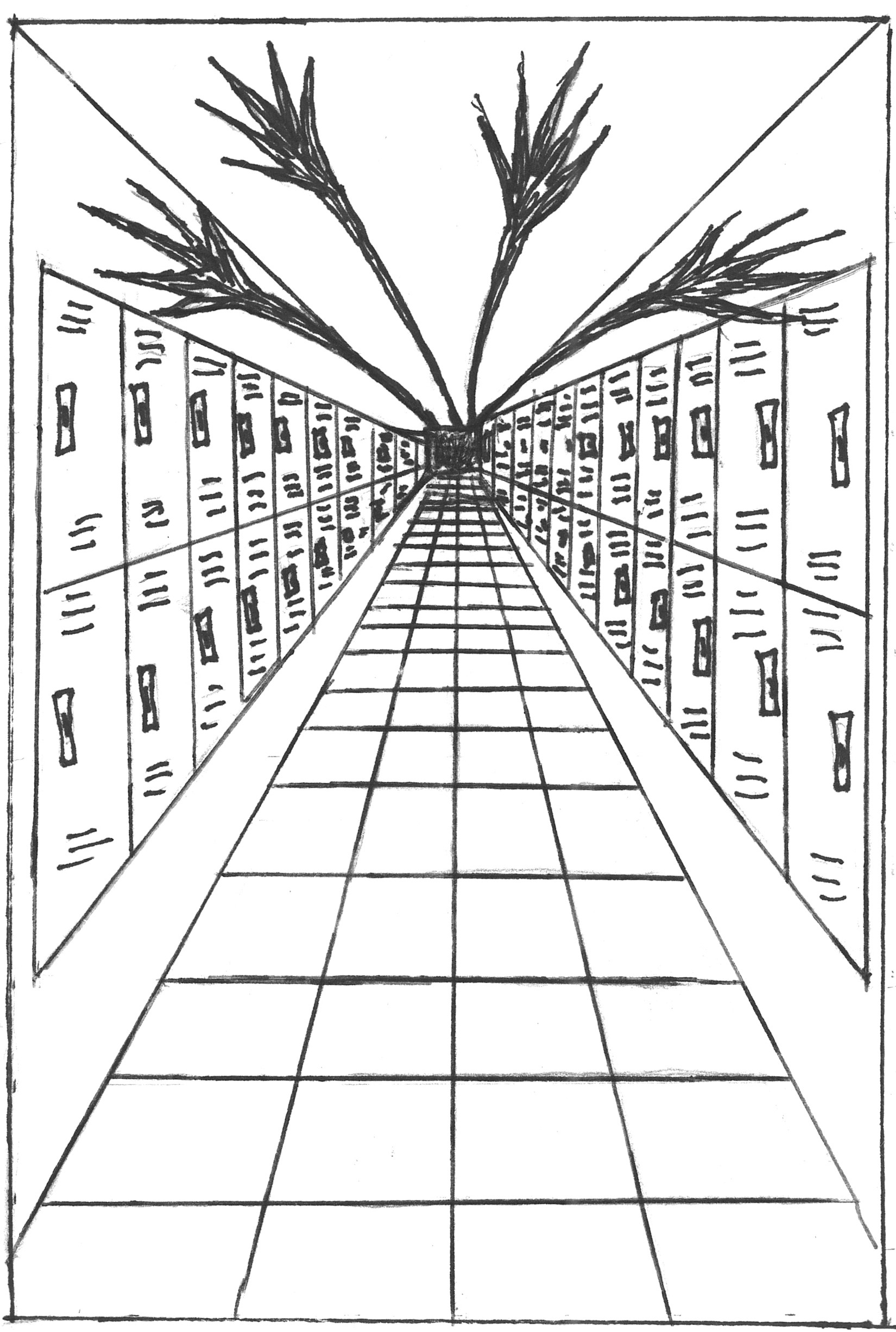

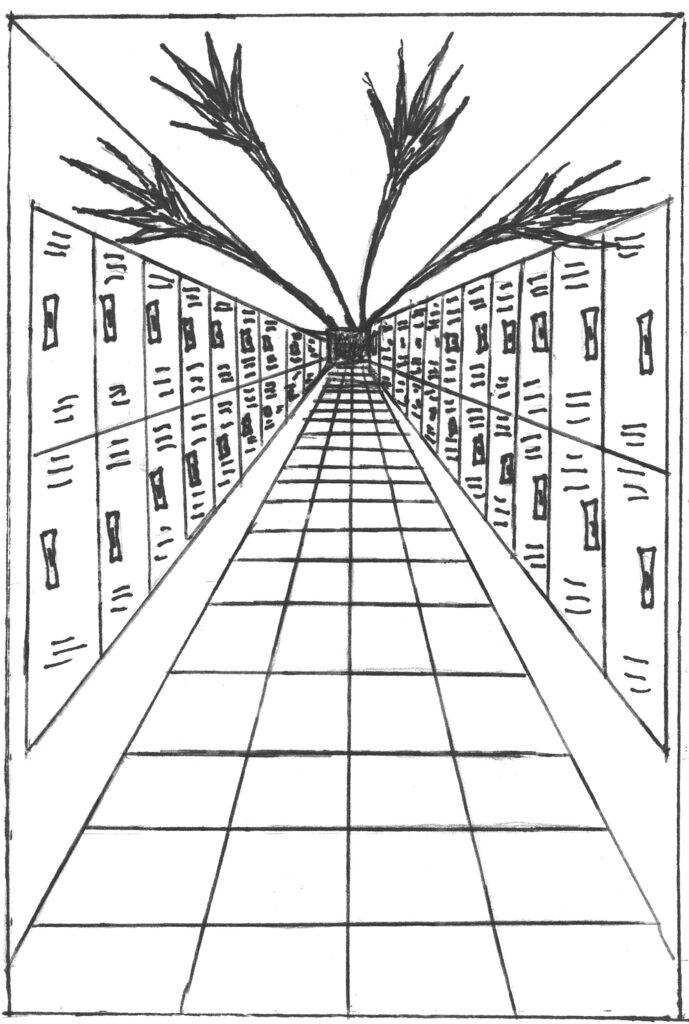

For these survivors, the school feels like a haunted house, with unknowns each time they turn down a hallway. Three Roosevelt students who identify as survivors of sexual assault shared their stories, all of whom have chosen to remain anonymous. One interviewee comments on the school atmosphere they have experienced, and says, “I kind of feel like a deer in headlights sometimes.”

Some students are forced to put extra precautions into their daily lives. One interviewee says, “I take a certain path in each of my classes to ensure I don’t run into people that I don’t want to.”

Another Roosevelt student described it as a constant fear, saying she’s constantly asking herself, “If I go here, will I see him? If I go here? Will I see ‘you know who’ and just being terrified.”

Some students have publicly shared their story on social media or with close friends. Some are walking the halls holding their experiences in secret.

Their friends and allies often don’t know what to do when dealing with instances of sexual assault. When asked what Roosevelt students can do, one student says, “Listen. If a friend tells you, know that it’s 15 million times harder to say it than it is to hear it.”

One interviewee urges the Roosevelt community to cut ties with any accused abusers. “Stop talking to them. Or, if you want to say one more thing, you can say I’m not going to talk to you anymore because I heard this. So unless this is proven false, I’m not going to interact with you.”

When people talked about sharing their stories, they reported mixed reactions from the Roosevelt community. One interviewee, though, reported an “undeniable support, and camaraderie” from other women at Roosevelt.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 10% of high school students were sexually assaulted in 2017, with females (15%) experiencing higher rates than males (4.3%).

When students are first exposed to sexual harassment and assualt, especially within their own peer group, many are left wondering how to understand such a complex subject in practical terms.

The three nterviewees were asked if they think they have received adequate education on sexual assault. All interviewees said no. “It’s not just like textbook assault, you know, it’s like coercion and all different forms of assault, because the only thing that I’ve ever been taught about was the textbook rape,” stated one interviewee. Here, various contexts of sexual assault are referenced.

Coercion, for example, is unwanted sexual activity that is the product of pressure, tricks, threats, or force in a non-physical way. Coerced sexual assault happens frequently, with approximately one in six women and one in ten men experiencing coercion in their lifetime, according to the National Sexual Violence Research Center.

Other important aspects of sexual violence could include power imbalances, age differences, and the use of drugs and alcohol.

Females aged 16-19 are four times more likely than the general population to be victims of rape, attempted rape, or sexual assault, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN). The likelihood is even higher if the person is queer or a person of color. This means that a large portion of the Roosevelt population is at risk.

The epidemic of sexual assault is here, but some feel that the necessary response from peers and educators isn’t.

Roosevelt health teacher Trina Norris discussed sexual assault education at Roosevelt, emphasizing her difficulty teaching extensively on sexual assault due to time restraints, particularly due to COVID.

Norris feels that beyond what she hears in the classroom, there isn’t much she can do to change the way students act or behave, “I can plant the seed, and I can call it out when I hear it, but when I don’t hear it there isn’t a whole lot I can do.”

Norris believes that the reporting system needs to be well known, “I think we need to be better at communicating to students, regardless of what the issue is, about what schools can and cannot do legally. I think that was where we kind of went wrong…” In some assault investigations, explains Norris, “we don’t get to know what the outcome was, it was actually illegal to share it. But I think somebody should have just communicated.” Norris presented how much progress she’s seen in her lifetime and has hope for the future, “I think there is hope though.”

Perhaps in part because of the legal restrictions on releasing investigation results, some students fear inaction following an assault report. All three survivors interviewed for this article chose not to report for this reason.

An anonymous interviewee said they felt as if people stopped putting in effort to support survivors when the in-person school year began. “Over COVID, when everyone was sharing their stories, everyone was so supportive […] But now that we’re back in person, I feel like you actually have to personally show that support.”

Alongside the stress of sharing hallways with their abusers, survivors are left feeling like the people around them don’t care.

Interviewees urge their peers to prioritize talking about sexual assault, even if it it can be daunting, as supporting survivors should always be a priority. They continue, “I don’t want to have to jump every time someone comes behind me or constantly be on edge. But I am and I didn’t get to choose that for me. None of us did. They made that decision for us. And there’s nothing that we can do to change that decision.”

The impact of a sexual assault on mental health is detrimental, with survivors of childhood sexual assault being four times more likely to develop symptoms of drug abuse, four times more likely to experience PTSD as adults, and three times more likely to experience a major depressive episode as adults. If you need help, call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 1-800-656-4673.