Across the country, public schools have struggled with equitably providing Section 504 accommodations—an issue from which Seattle Public Schools (SPS) is not exempt.

SPS Student Supports 504 and ADA Coordinator Shanon Lewis elaborates that part of the role of 504 accommodations is to “[level] the playing field for students with disabilities so they [can] show their true intelligence.”

Increasing access to opportunity is a key component of a Section 504 Plan. Accommodations are meant to provide educational support for disabled students and allow for equitable access to a fair and free education, as explained by PAVE (Partnerships for Action, Voices for Empowerment), a support organization for families impacted by disabilities.

Frank Heffernan, Roosevelt counselor and 504 Building Coordinator, says, “[504s are] designed to help people stay on the deck of the boat, and be successful in an average way with their peers.”

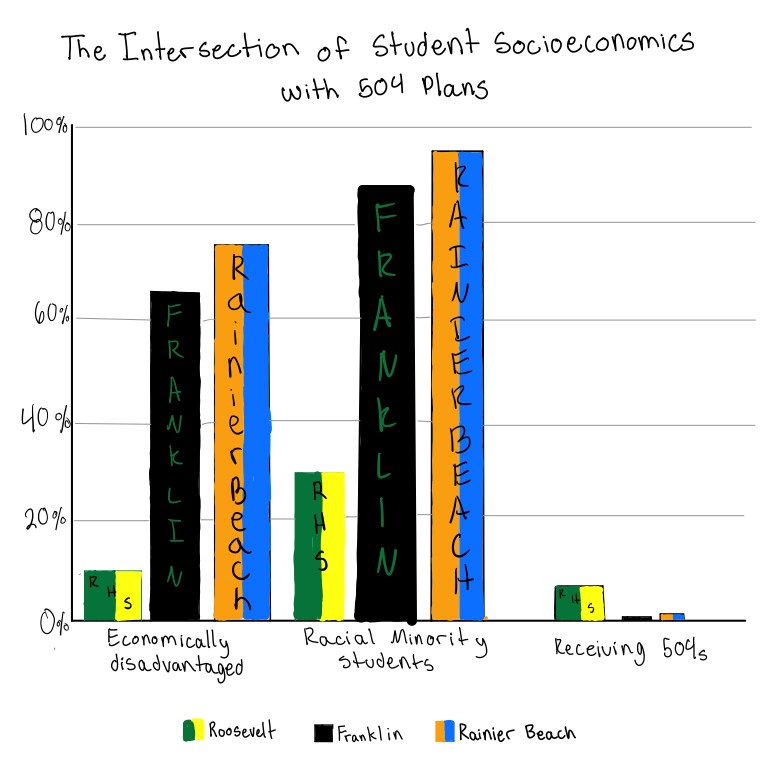

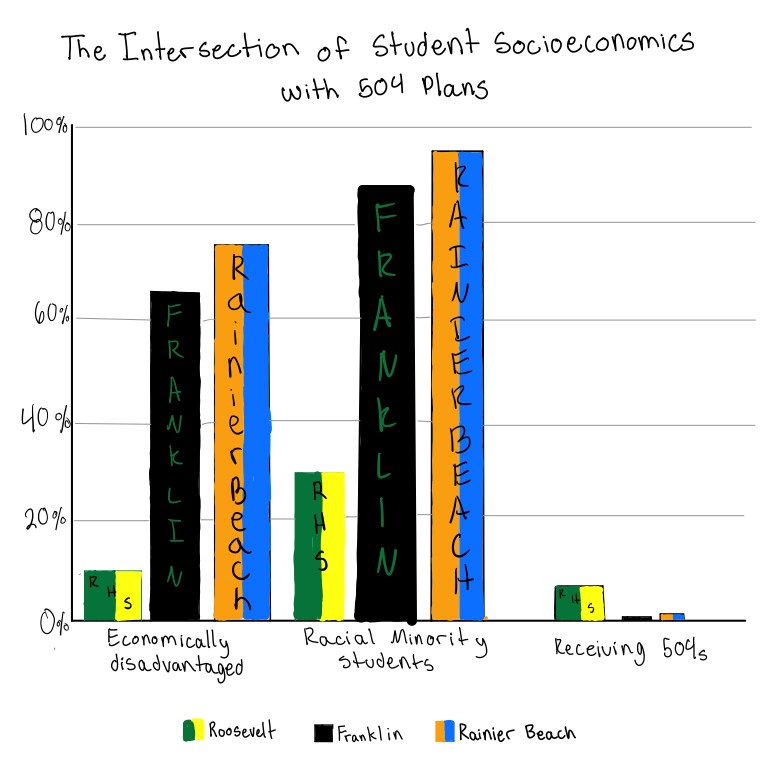

Yet SPS demographic data reveals large inequities across which groups are able to access 504 Plans. Roosevelt High School, one of the district’s wealthiest schools, has one of the highest proportions of its student body receiving accommodations, standing starkly against Franklin High School and Rainier Beach High School.

In fact, 7.7% of the Roosevelt student body receive such accommodations, according to 2017 findings from the Civil Rights Data Collection. Meanwhile, only 0.8% of Franklin students and 1.2% of Rainier Beach students are supported by a 504 Plan.

Data from U.S. News outlines the wealth and demographics of these schools. At Roosevelt, 10% of enrolled students are economically disadvantaged, and 30% are racial minority students. Comparatively, 65% of students are economically disadvantaged at Franklin, and 90% are minorities. Further, Rainier Beach has a student body that is 75% economically disadvantaged, and 97.4% of which are minorities.

Heffernan comments on the high number of Roosevelt students being served by 504s, saying, “It’s probably fair to say that [Roosevelt], percentage wise, probably [has] more 504s in the building than potentially we need or should.”

Heffernan continues by asking “Why are there such a high percentage of students in one building that need a 504, when that’s not the case in other high schools across the city?”

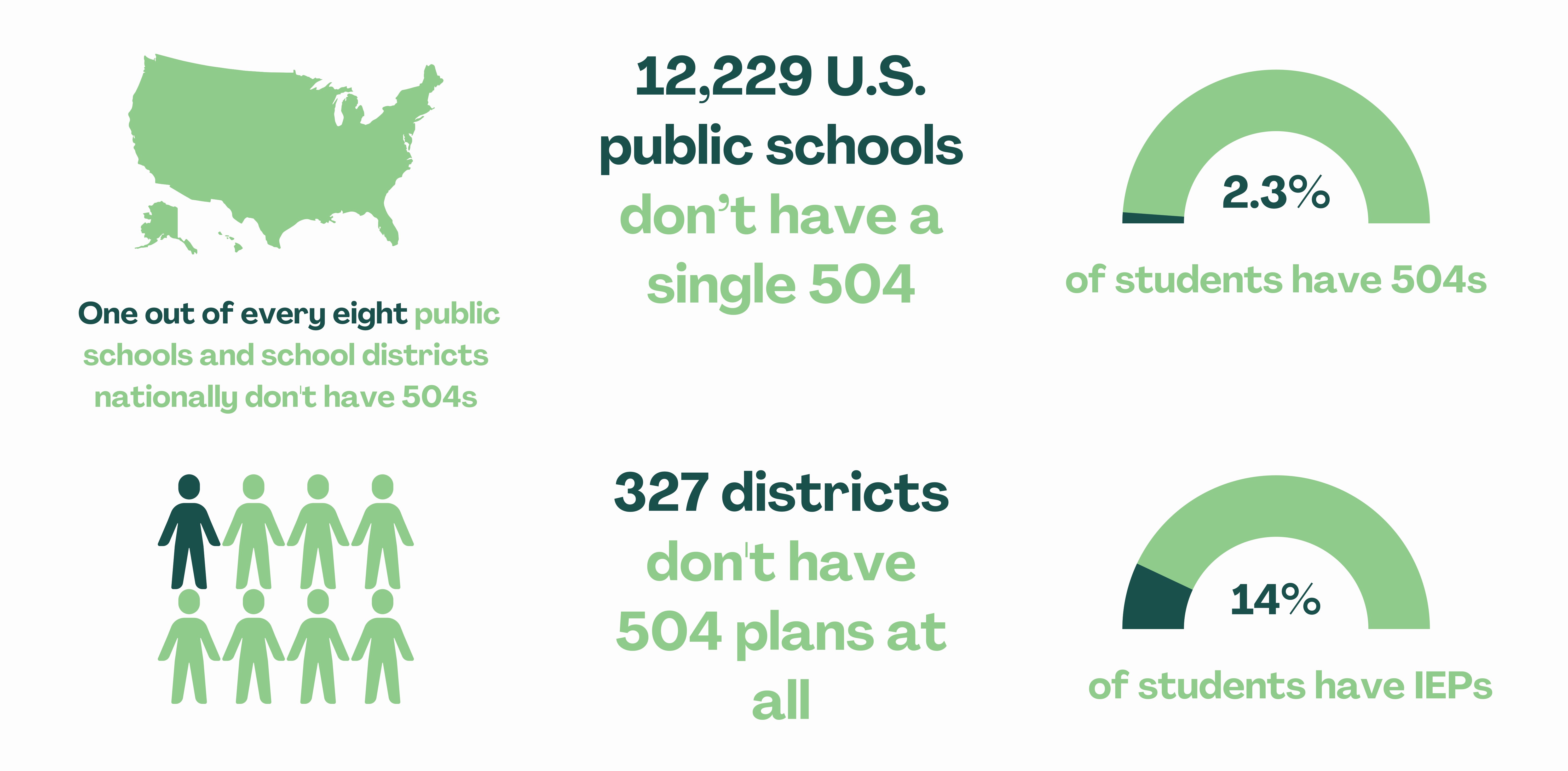

504s concentrated in majority white schools is not unique to SPS. The Advocacy Institute provides evidence to demonstrate nationwide overrepresentation of white students: while 51.7% of students in the U.S. are white, they make up 65% of students served by 504s.

How wealth and race play into 504 access

While 504 accommodations are meant to be accessible, access to wealth and resources have given affluent families a leg up in the system. Data from the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances reveals that the average white family “has eight times the wealth of the typical Black family and five times the wealth of the typical Hispanic family.”

The New York Times elaborates on the resources wealthy families can take advantage of: When a student’s grades are slipping, parents may turn to private practitioners for psychoeducational testing – a standard assessment of cognitive ability, academic performance, memory, and general behavior.

The price of such assessments ranges from $2,000 to $5,000, and can take from two weeks to several months. Mindprint Learning finds that health insurance may cover a part of the evaluation cost for psychological disorders (e.g. anxiety, depression, ADHD), but usually doesn’t cover the cost of an educational or learning challenge.

On the other hand, low-income students without the resources to independently access psychological testing rely on school systems to identify and assist their disabilities. LAist explains, “In practice, this can mean waiting for the school to notice shortcomings or battling through the bureaucracy of the public school system to get an evaluation — a longer and more difficult process than paying for private psychological testing.”

To further cement this, 2015-16 data from the U.S. Census and Department of Education outlines that schools in the top 1% of median household income had a 5.8% rate of 504 Plans, compared to the national average of 2.7%. Conversely, schools in the bottom 1% of household income had a 1.5% rate of 504 Plans.

In other words, wealthy students are receiving more accommodations.

And yet, both Lewis and Heffernan stress that a diagnosis is never necessary to make a 504 request.

So where does the issue lie? There are two possibilities.

One, affluent families are taking advantage of the system to unfairly benefit their children. However, beyond extreme examples such as the “Varsity Blues” college admissions fraud orchestrated by William “Rick” Singer, there is little evidence to support a widespread trend of wealthy families unethically obtaining 504 accommodations.

A second possibility is that wealthy families simply have the resources and time to address their children’s academic needs. The Arizona Daily Star explains how parents who lack the time or language proficiency skills struggle to learn about 504 Plans, research civil rights laws, or afford the aid of professionals.

Heffernan explains Roosevelt’s disproportionate number of 504 Plans in comparison to other SPS schools as an issue of wealth disparity. “It’s probably a socioeconomic thing, people are more savvy about the system perhaps,” he says. “Maybe if your parents are educated and are able to navigate the processes of a bureaucracy like the school district and all that goes into that, they’re going to be, potentially, more knowledgeable about how to request accommodations for students.”

The shortcomings of 504 systems

The mandatory ‘Child Find’ program is meant to circumvent the socio-economic accessibility gap.

According to the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting, Section 504 requires schools to be responsible for actively identifying students in need of 504 services, informing parents of the evaluation process, and seeking permission to perform such an evaluation.

At Roosevelt, Child Find initiatives largely take place in the fall. Lewis explains Roosevelt’s Child Find form, also known as a 504-2, is “in the first week package. Your front office should have a copy of it, it’s also on the SPS website. It has a cover letter explaining to parents and it comes in five or seven different languages.”

SPS’s Child Find procedures are concentrated at the start of the first semester. For the rest of the year, staff, parents, and students are responsible for requesting a 504.

However, in many cases, this form of Child Find — which is a standard process across the SPS district — is not extensive enough. According to Heffernan, teachers rarely put in a 504 request for a student who they may have identified as needing accommodations based on their performance in their class. “Historically,” he says, “it’s always been the parent who’s come forward.”

“The problem is that at Roosevelt, we want to help all students be successful, as a staff. And there’s a limited bandwidth of how much time and energy any one school counselor or support staff have to work with students, it’s 400+ to 1 ratio,” Heffernan says.

He continues, “There’s probably lots of kids in this building that could benefit from support services, but they don’t come forth on their own asking for them at quite the same level as other members of the community. And so … there may be an imbalance in services just because of the demand on the school to serve students who have a voice.”

A second major shortcoming is the lack of financial support for 504 programs. Unlike the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Section 504 does not require that the federal government allocate funding for the programs and services associated with Section 504 compliance.

It is for this reason that Charles Russo and Timothy Morse of LD OnLine explain that districts often absorb ‘hidden costs’ when providing 504 accommodations and processing requests, many of which are frequently difficult to quantify.

For example, Russo and Morse argue that, for teachers and other personnel involved in evaluating students, complying with Section 504 may require substantial uncompensated time spent on “[determining] whether a child is eligible for services under Section 504, writing Section 504 individual accommodation plans, and resolving disputes about the delivery of educational services.”

This being said, Lewis states that her department does not have undue financial burden. “My department is not turned down for running out of money,” she says. “It is fully funded for what we have.” Among other things, she says that her department has been “supplying tutors for students with 504” and has “increased our budget knowing that students coming back from COVID would need to have extra support.”

Data from the U.S. government’s Civil Rights Data Collection, Perry Zirkel, Ph.D., Lehigh University (2015-16)

What are the solutions?

Yet for other schools across the state and nationwide, adequate funding may not be their reality. It is for this reason that initiatives aimed at increasing access to 504 Plans must involve a redistribution of funds. The Center for American Progress (CAP), a progressive nonpartisan policy institute, outlines three recommendations to bridge the gap in 504 access.

First, CAP advocates for increasing targeted funding to the Center for Parent Information and Resources to improve outreach to marginalized communities. Efforts should focus on “eliminating the knowledge gap” — the lack of 504 knowledge among low-income families, how to obtain access to the service, and their legal rights — while ensuring culturally appropriate resources. This could mean translating educational materials into more diverse languages, expanding access to linguistic minorities.

Funding should also be redirected to counselors, therapists, and other accessible support services. The investment of federal funding for this purpose is key, especially within schools with limited tax revenue from low-income communities. Further, CAP emphasizes the need to hire specialists that are representative of the student body, noting that “When students see people who represent their identities, they are more likely to feel satisfied with treatment and the outcome of those services.”

This said, improved resources to remove the educational barrier to receiving plans must come in tandem with proactive enforcement of Section 504, both on the local and federal level. CAP finds that while the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights is responsible for 504 enforcement, tasked with investigating institutions that have potentially failed to provide services and identify students in need under 504 law — yet the department “rarely issues penalties or even launches compliance investigations.” Since 1984, there have only been 200 investigations of this nature.

Beyond greater enforcement of Section 504’s Child Find policy, universal screening measures is another option to identify students in need of a 504. In Georgia, public schools are required to screen all kindergarteners for dyslexia, in addition to any students from first through third grade who exhibit signs of a learning disability.

Within SPS, Lewis outlines some other potential outreach efforts that are currently being considered once the pandemic wanes and in-person events are safer. “We were in the path of putting together a group of students who already had 504 Plans, a couple from each of the high schools, to kind of be a peer group and a sounding board,” she says. “We are reaching out to building coordinators and letting them know once we’re out there if there are students that would like to come in and meet with us and discuss 504, the process, and how 504 is effective for them — that we were available.”

Beyond this, Lewis says, “We’ve talked about doing a 504 newsletter, but I’m a department of only two people for close to 3,000 students.”

While numerous methods are being discussed to close the knowledge gap and strengthen Child Find initiatives, one thing is clear: There is a clear disparity across SPS regarding who has the means to access 504 accommodations.