I am half-Mexican, and half-white.

According to the official documents, I am white.

According to society, I am Mexican.

I’m not alone. We say this country is a melting pot with pride, but we are still blind to the complexities of racial identities in this contemporary world. We read statistics about racial demographics as if they are that easy, as if people fit into categories that quickly. As if there is only one way to be black, one way to be Latino, one way to be white. It’s not that simple. And for the mixed race population, it’s especially complicated.

Until 2000, the US Census Bureau didn’t allow people to choose more than one racial category while filling out the Census. Even now, many forms I’ve filled out in my life have not allowed me to pick more than one. I am forced to choose one ethnicity over the other, but this feels morally amiss. I’m not comfortable discarding one side of my family. My only other option is to pick “other” but this erases my identity completely.

Even the forms that allow me to pick more than one category are difficult to navigate. For any mixed person or any person at all, it’s challenging to figure out where you fit. The categories are too static and clearcut and they’re completely illogical. A Middle Easterner, a North African, and a Latino are all technically racially white under these rules. For me in particular, that last one is alarming. I am allowed to check off my ethnicity as Hispanic, but when the race choices come up, there is no option for being Hispanic. Hispanic isn’t a race. Therefore, any Hispanic person in the entire world is actually racially white. So that’s the answer I’m forced to pick, however wrong it feels.

For any mixed person or any person at all, it’s challenging to figure out where you fit.

It’s fair to say that Middle Easterners, North Africans, and Latinos are usually not considered white in daily life. They do not get to receive any of the societal benefits of whiteness. Instead, they get all the discrimination of being non-white, while being denied representation in the numbers. All those statistics we cite over and over again, about how white Roosevelt is, about the racial make ups of our neighborhoods, now seem far less accurate. Is Roosevelt actually 67% white? Only 7% multiracial? I have my doubts. Those numbers seem beyond skewed, and they do not demonstrate the true diversity that this community holds.

Yet while our misrepresentations of diversity are annoying, even at times offensive, nothing hurts me as much as being told by someone who I identify with that I shouldn’t. My white peers assume I share no cultural background with them, only to discover I had afternoon tea with my Irish-Canadian great-grandmother and listen to her talk about her family fleeing the potato famine. Most people think that kind of story is not synonymous with my skin color. In seventh grade, a Mexican classmate told me that because I was only half and I didn’t speak Spanish at home, I wasn’t a “real Mexican.” These things are far worse than any racist comment I’ve ever heard. As terrible as it is to be discriminated against for your identity, it is twenty times worse to be denied your identity at all.

As terrible as it is to be discriminated against for your identity, it is twenty times worse to be denied your identity at all.

We should all be able to identify as we wish. But for many mixed race people, the choice is made for them. I’m Mexican to most people. As proud as I am of my Mexican family’s story and their perseverance in this country, the fact is that my white side of the family was one of the original settlers of 17th century Connecticut, and we fought in every single American war throughout history. At home, I identify with both sides of my family equally. Out in the world, I’m forced to be Mexican. But sometimes not even that is true, not when other Latinos remind me that I’m not the same as them, and somehow less legitimate.

So I can’t be white, and I can’t be Mexican. To the forms, I’m ethnically Hispanic, and racially white, but this means I fill out the same bubbles as someone who is 100% Hispanic. Once again, my identity is lost. Race and ethnicity is not simple. Race and ethnicity is complicated. Most people call it a social construct, but it becomes very real when our schools and our government force us to fill out forms that make it tangible and help them make assumptions based off numbers that have no meaning. We as a society have not equipped ourselves to deal with mixed race people, choosing instead to speak about race in the simplest possible terms, to make racism and discrimination fit into easy little boxes, to ignore the complexities so we don’t have to think as hard. We are comfortable acknowledging racism only in the lowest possible denominators, using racial stereotypes that remain within our convenient norms. A Latina’s skin is too light, an Asian’s hair is not dark enough, a black person speaks too eloquently.But in this world, not post-racial but post-racial “purity” it is impossible to look at someone and accurately ascertain their background. Skin color has never been a foolproof way of determining identity. But we continue to use it, in ignorance, out of habit, due to the unrelenting racial reasoning that we perpetrate without thinking. We should never look at someone and think that we know their story. Even if we think their skin is so obviously white or so evidently black, we can never know where their family comes from, what they identify as, what traditions they follow. And in a world where mixed populations are skyrocketing, we need to understand that this kind of racial simplification is completely illogical.

I see mixed people everywhere. When I bring this topic up, there is no shortage of people who can understand. Even people who aren’t mixed race can connect to the idea of conflicting identities and they join the conversation as well. We are clamoring to have this discussion. We are desperate to have our identities legitimized as we move through a world which still seems to see race as “pure” and doesn’t accept the mixing of cultures. We are continually forced to segregate within our own selves in order to fit into this society. We have to choose one identity over the other because otherwise we cannot function or conform to the comfortable standards that most people would like to live by, where there is black and white and nothing else. Our own school district classified people as only white or non-white up until 2008. I can’t help but wonder which category they put me into.

No one culture is so significantly separate from another that they cannot be connected in some way.

The willful ignorance that crams us into boxes doesn’t make sense to my everyday interactions. It extends beyond race and into ethnicities and nationalities and cultures. No one culture is so significantly separate from another that they cannot be connected in some way. An Irish immigrant uses the same language my Mexican grandmother uses in describing the fear of losing one’s identity when they move to a new country. A white counterpart assumes my family has no investment in US history, when my ancestors probably fought right alongside theirs in World War II. A Chinese American shares the struggles of not looking stereotypical enough to fit the expectations of other Chinese Americans. A person can be Swedish, German, Spanish and French and have a vast family history behind them, but we just call them white. A black girl and I, both with curly hair, complain about people assuming they have permission to touch it. A Jewish Korean celebrates finding a Japanese Jew. Being mixed is about more than race. It is the mixing of cultures and identities that no longer fit into categories that seek only to homogenize. Our own president is a half-Kenyan, half-white guy that grew up in Hawaii and Indonesia. When he fills out forms and picks the “white” and “black” options, there’s a lot that’s not being told. That is what this kind of thinking brings about. It denies us our identities. Our stories are mixed, no matter how standard our skin tone is, and they cannot be told by checking off boxes.

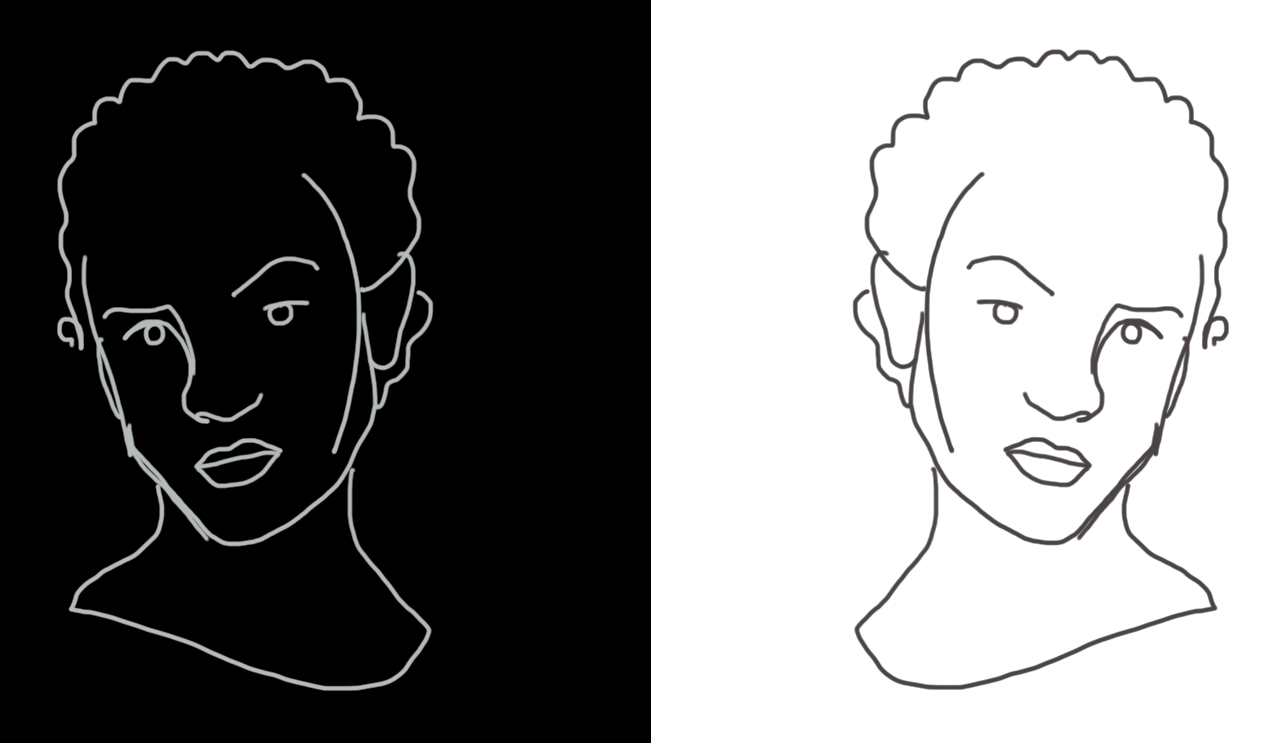

Featured Picture: In many cases, a person’s race doesn’t tell their whole story. Picture by Xing Gilbert